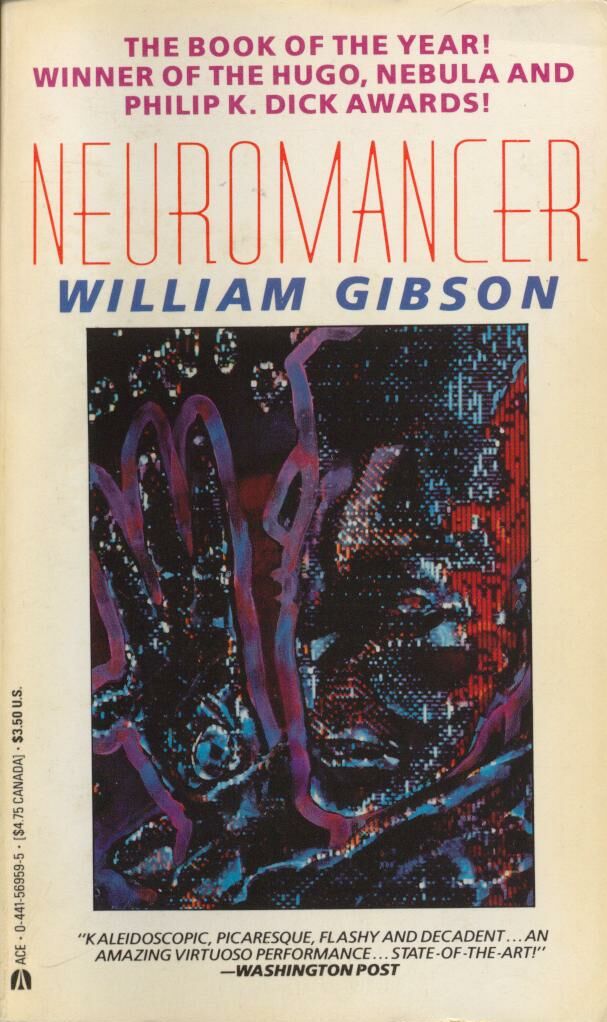

William Gibson. Neuromancer

THE CRITICS RAVE ABOUT NEUROMANCER. . .

"Neuromancer is freshly imagined, compellingly detailed and chiling..."

-- The New York Times

"UNFORGETTABLE. . . The richness of Gibson's world is

incredible!"

-- Chicago Sun-Times

"SUPERB! Gibson has created a rich, detailed, and vivid near future,

populated with uncomfortably realistic characters . . . an amazingly comples

novel . . . Some will enjoy it as a fast-paced, exciting adventure; others

will claim it's actually a very subtle, clever mystery; still others

will see it as a thought-provoking social discourse. . . Neuromancer IS A

MAJOR NOVEL, difficult to compare with other works for the simple reason

that it really is new, and different . . . HIGHLY RECOMMENDED!"

-- Fantasy Review

"A flashy tour of a remarkably well-visualized future. . . Gibson

manufactures wild details with a virtuoso's glee. . . an impressive

new voice!"

-- Newsday

"WILLIAM GIBSON IS A WELCOME NEW TALENT!"

-- Locus

A SIGNIFICANT ACHIEVEMENT! William Gibson's Neuromancer is one of

the finest first novels of the last few years, and may be the only science

fiction novel which has combined hard science. . .and a well-developed

sensibility to produce a kind of high-tech punk novel."

-- Norman Spinrad

"Science Fiction of exceptional texture and vision. . .Gibson opens up

a new genre, with a finely crafted grittiness, with a number of literary and

computer inventions that may well stick. . .SHEER PLEASURE!"

Stewart Brand, San Francisco Chronicle

"A crowd-pleaser as well as a finely crafted piece of literature. . .

The book deserves immense popularity. . . READ IT!"

-- Edward Bryant, Mile High Futures

"A MINDBINDER OF A READ. . . fully realized in its geopolitical,

technological and, psychosexual dimensions. . ."

-- Village Voice

"William Gibson is one of the most excited new writers to hit science

fiction in a long time. His first novel is an event I've been eagerly

awaiting."

-- Robert Silverberg

"William Gibson's Neuromancer. . . brings an entirely new

electronic punk sensibility to SF, both in content and prose style. It has

been a long time indeed since a first novel established such a new and

unusual voice with this degree of strength and surety."

-- Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine

"Say goodbye to your old stale futures. Here is an entirely realized

new world, intense as an electric shock. William Gibson's prose,

astonishing in it's clarity and skill, becomes high-tech electronic poetry.

. . An enthralling adventure story, as brilliant and coherent as a laser.

THIS IS WHY SCIENCE FICTION WAS INVENTED!"

-- Bruce Sterling

Ace books by William Gibson

BURNING CHROME COUNT ZERO MONA LISA OVERDRIVE

This book was first published as an Ace Science Fiction original

edition. The first through third printings were as as an Ace Science Fiction

Special, edited by Terry Carr. A limited hardcover edition was published by

Phantasia Press in the Spring of 1986.

NEUROMANCER

An Ace Book / published by arrangement with the author

PRINTING HISTORY Ace edition / July 1984

All rights reserved. Copyright © 1984 by William Gibson Cover art

by Richard Berry This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by

mimeograph or any other means, without permission. For information address:

The Berkley Publishing Group, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

ISBN: 0-441-56959-5

Ace books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group, 200 Madison

Avenue, New York, New York 10016. The Name "Ace" and the "A" logo are

trademarks belonging to Charter Communications, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Dedication: for Deb

who made it possible

with love

THE CRITICS RAVE ABOUT NEUROMANCER. . .

"Neuromancer is freshly imagined, compellingly detailed and chiling..."

-- The New York Times

"UNFORGETTABLE. . . The richness of Gibson's world is

incredible!"

-- Chicago Sun-Times

"SUPERB! Gibson has created a rich, detailed, and vivid near future,

populated with uncomfortably realistic characters . . . an amazingly comples

novel . . . Some will enjoy it as a fast-paced, exciting adventure; others

will claim it's actually a very subtle, clever mystery; still others

will see it as a thought-provoking social discourse. . . Neuromancer IS A

MAJOR NOVEL, difficult to compare with other works for the simple reason

that it really is new, and different . . . HIGHLY RECOMMENDED!"

-- Fantasy Review

"A flashy tour of a remarkably well-visualized future. . . Gibson

manufactures wild details with a virtuoso's glee. . . an impressive

new voice!"

-- Newsday

"WILLIAM GIBSON IS A WELCOME NEW TALENT!"

-- Locus

A SIGNIFICANT ACHIEVEMENT! William Gibson's Neuromancer is one of

the finest first novels of the last few years, and may be the only science

fiction novel which has combined hard science. . .and a well-developed

sensibility to produce a kind of high-tech punk novel."

-- Norman Spinrad

"Science Fiction of exceptional texture and vision. . .Gibson opens up

a new genre, with a finely crafted grittiness, with a number of literary and

computer inventions that may well stick. . .SHEER PLEASURE!"

Stewart Brand, San Francisco Chronicle

"A crowd-pleaser as well as a finely crafted piece of literature. . .

The book deserves immense popularity. . . READ IT!"

-- Edward Bryant, Mile High Futures

"A MINDBINDER OF A READ. . . fully realized in its geopolitical,

technological and, psychosexual dimensions. . ."

-- Village Voice

"William Gibson is one of the most excited new writers to hit science

fiction in a long time. His first novel is an event I've been eagerly

awaiting."

-- Robert Silverberg

"William Gibson's Neuromancer. . . brings an entirely new

electronic punk sensibility to SF, both in content and prose style. It has

been a long time indeed since a first novel established such a new and

unusual voice with this degree of strength and surety."

-- Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine

"Say goodbye to your old stale futures. Here is an entirely realized

new world, intense as an electric shock. William Gibson's prose,

astonishing in it's clarity and skill, becomes high-tech electronic poetry.

. . An enthralling adventure story, as brilliant and coherent as a laser.

THIS IS WHY SCIENCE FICTION WAS INVENTED!"

-- Bruce Sterling

Ace books by William Gibson

BURNING CHROME COUNT ZERO MONA LISA OVERDRIVE

This book was first published as an Ace Science Fiction original

edition. The first through third printings were as as an Ace Science Fiction

Special, edited by Terry Carr. A limited hardcover edition was published by

Phantasia Press in the Spring of 1986.

NEUROMANCER

An Ace Book / published by arrangement with the author

PRINTING HISTORY Ace edition / July 1984

All rights reserved. Copyright © 1984 by William Gibson Cover art

by Richard Berry This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by

mimeograph or any other means, without permission. For information address:

The Berkley Publishing Group, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

ISBN: 0-441-56959-5

Ace books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group, 200 Madison

Avenue, New York, New York 10016. The Name "Ace" and the "A" logo are

trademarks belonging to Charter Communications, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Dedication: for Deb

who made it possible

with love

* PART ONE. CHIBA CITY BLUES

The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead

channel.

"It's not like I'm using," Case heard someone say, as he

shouldered his way through the crowd around the door of the Chat.

"It's like my body's developed this massive drug deficiency." It

was a Sprawl voice and a Sprawl joke. The Chatsubo was a bar for

professional expatriates; you could drink there for a week and never hear

two words in Japanese.

Ratz was tending bar, his prosthetic arm jerking monotonously as he

filled a tray of glasses with draft Kirin. He saw Case and smiled, his teeth

a web work of East European steel and brown decay. Case found a place at the

bar, between the unlikely tan on one of Lonny Zone's whores and the

crisp naval uniform of a tall African whose cheekbones were ridged with

precise rows of tribal scars. "Wage was in here early, with two Joe boys,"

Ratz said, shoving a draft across the bar with his good hand. "Maybe some

business with you, Case?"

Case shrugged. The girl to his right giggled and nudged him.

The bartender's smile widened. His ugliness was the stuff of

legend. In an age of affordable beauty, there was something heraldic about

his lack of it. The antique arm whined as he reached for another mug. It was

a Russian military prosthesis, a seven-function force-feedback manipulator,

cased in grubby pink plastic. "You are too much the artiste, Herr Case."

Ratz grunted; the sound served him as laughter. He scratched his overhang of

white-shirted belly with the pink claw. "You are the artiste of the slightly

funny deal."

"Sure," Case said, and sipped his beer. "Somebody's gotta be

funny around here. Sure the fuck isn't you."

The whore's giggle went up an octave.

"Isn't you either, sister. So you vanish, okay? Zone, he's

a close personal friend of mine."

She looked Case in the eye and made the softest possible spitting

sound, her lips barely moving. But she left. "Jesus," Case said, "what kind

a creep joint you running here? Man can't have a drink."

"Ha," Ratz said, swabbing the scarred wood with a rag, "Zone shows a

percentage. You I let work here for entertainment value."

As Case was picking up his beer, one of those strange instants of

silence descended, as though a hundred unrelated conversations had

simultaneously arrived at the same pause. Then the whore's giggle rang

out, tinged with a certain hysteria.

Ratz grunted. "An angel passed."

"The Chinese," bellowed a drunken Australian, "Chinese bloody invented

nerve-splicing. Give me the mainland for a nerve job any day. Fix you right,

mate. . ."

"Now that," Case said to his glass, all his bitterness suddenly rising

in him like bile, "that is so much bullshit."

The Japanese had already forgotten more neurosurgery than the Chinese

had ever known. The black clinics of Chiba were the cutting edge, whole

bodies of technique supplanted monthly, and still they couldn't repair

the damage he'd suffered in that Memphis hotel.

A year here and he still dreamed of cyberspace, hope fading nightly.

All the speed he took, all the turns he'd taken and the corners

he'd cut in Night City, and still he'd see the matrix in his

sleep, bright lattices of logic unfolding across that colorless void. . .

The Sprawl was a long strange way home over the Pacific now, and he was no

console man, no cyberspace cowboy. Just another hustler, trying to make it

through. But the dreams came on in the Japanese night like live wire voodoo

and he'd cry for it, cry in his sleep, and wake alone in the dark,

curled in his capsule in some coffin hotel, his hands clawed into the

bedslab, temperfoam bunched between his fingers, trying to reach the console

that wasn't there.

"I saw your girl last night," Ratz said, passing Case his second Kirin.

"I don't have one," he said, and drank.

"Miss Linda Lee."

Case shook his head.

"No girl? Nothing? Only biz, friend artiste? Dedication to commerce?"

The bartender's small brown eyes were nested deep in wrinkled flesh.

"I think I liked you better, with her. You laughed more. Now, some night,

you get maybe too artistic, you wind up in the clinic tanks, spare parts."

"You're breaking my heart, Ratz." He finished his beer, paid and

left, high narrow shoulders hunched beneath the rain-stained khaki nylon of

his windbreaker. Threading his way through the Ninsei crowds, he could smell

his own stale sweat.

Case was twenty-four. At twenty-two, he'd been a cowboy a

rustler, one of the best in the Sprawl. He'd been trained by the best,

by McCoy Pauley and Bobby Quine, legends in the biz. He'd operated on

an almost permanent adrenaline high, a byproduct of youth and proficiency,

jacked into a custom cyberspace deck that projected his disembodied

consciousness into the consensual hallucination that was the matrix. A thief

he'd worked for other, wealthier thieves, employers who provided the

exotic software required to penetrate the bright walls of corporate systems,

opening windows into rich fields of data.

He'd made the classic mistake, the one he'd sworn

he'd never make. He stole from his employers. He kept something for

himself and tried to move it through a fence in Amsterdam. He still

wasn't sure how he'd been discovered, not that it mattered now.

He'd expected to die, then, but they only smiled. Of course he was

welcome, they told him, welcome to the money. And he was going to need it.

Because – still smiling – they were going to make sure he never

worked again.

They damaged his nervous system with a wartime Russian mycotoxin.

Strapped to a bed in a Memphis hotel, his talent burning out micron by

micron, he hallucinated for thirty hours.

The damage was minute, subtle, and utterly effective.

For Case, who'd lived for the bodiless exultation of cyberspace,

it was the Fall. In the bars he'd frequented as a cowboy hotshot, the

elite stance involved a certain relaxed contempt for the flesh. The body was

meat. Case fell into the prison of his own flesh.

His total assets were quickly converted to New Yen, a fat sheaf of the

old paper currency that circulated endlessly through the closed circuit of

the world's black markets like the seashells of the Trobriand

islanders. It was difficult to transact legitimate business with cash in the

Sprawl; in Japan, it was already illegal.

In Japan, he'd known with a clenched and absolute certainty,

he'd find his cure. In Chiba. Either in a registered clinic or in the

shadow land of black medicine. Synonymous with implants, nerve-splicing, and

micro bionics, Chiba was a magnet for the Sprawl's techno-criminal

subcultures.

In Chiba, he'd watched his New Yen vanish in a two-month round of

examinations and consultations. The men in the black clinics, his last hope,

had admired the expertise with which he'd been maimed, and then slowly

shaken their heads.

Now he slept in the cheapest coffins, the ones nearest the port,

beneath the quartz-halogen floods that lit the docks all night like vast

stages; where you couldn't see the lights of Tokyo for the glare of

the television sky, not even the towering hologram logo of the Fuji Electric

Company, and Tokyo Bay was a black expanse where gulls wheeled above

drifting shoals of white styrofoam. Behind the port lay the city, factory

domes dominated by the vast cubes of corporate arcologies. Port and city

were divided by a narrow borderland of older streets, an area with no

official name. Night City, with Ninsei its heart. By day, the bars down

Ninsei were shuttered and featureless, the neon dead, the holograms inert,

waiting, under the poisoned silver sky.

Two blocks west of the Chat, in a teashop called the Jarre de The, Case

washed down the night's first pill with a double espresso. It was a

flat pink octagon, a potent species of Brazilian dex he bought from one of

Zone's girls.

The Jarre was walled with mirrors, each panel framed in red neon.

At first, finding himself alone in Chiba, with little money and less

hope of finding a cure, he'd gone into a kind of terminal overdrive,

hustling fresh capital with a cold intensity that had seemed to belong to

someone else. In the first month, he'd killed two men and a woman over

sums that a year before would have seemed ludicrous. Ninsei wore him down

until the street itself came to seem the externalization of some death wish,

some secret poison he hadn't known he carried.

Night City was like a deranged experiment in social Darwinism, designed

by a bored researcher who kept one thumb permanently on the fast-forward

button. Stop hustling and you sank without a trace, but move a little too

swiftly and you'd break the fragile surface tension of the black

market; either way, you were gone, with nothing left of you but some vague

memory in the mind of a fixture like Ratz, though heart or lungs or kidneys

might survive in the service of some stranger with New Yen for the clinic

tanks.

Biz here was a constant subliminal hum, and death the accepted

punishment for laziness, carelessness, lack of grace, the failure to heed

the demands of an intricate protocol.

Alone at a table in the Jarre de The, with the octagon coming on,

pinheads of sweat starting from his palms, suddenly aware of each tingling

hair on his arms and chest, Case knew that at some point he'd started

to play a game with himself, a very ancient one that has no name, a final

solitaire. He no longer carried a weapon, no longer took the basic

precautions. He ran the fastest, loosest deals on the street, and he had a

reputation for being able to get whatever you wanted. A part of him knew

that the arc of his self-destruction was glaringly obvious to his customers,

who grew steadily fewer, but that same part of him basked in the knowledge

that it was only a matter of time. And that was the part of him, smug in its

expectation of death, that most hated the thought of Linda Lee.

He'd found her, one rainy night, in an arcade.

Under bright ghosts burning through a blue haze of cigarette smoke,

holograms of Wizard's Castle, Tank War Europa, the New York skyline. .

. And now he remembered her that way, her face bathed in restless laser

light, features reduced to a code: her cheekbones flaring scarlet as

Wizard's Castle burned, forehead drenched with azure when Munich fell

to the Tank War, mouth touched with hot gold as a gliding cursor struck

sparks from the wall of a skyscraper canyon. He was riding high that night,

with a brick of Wage's ketamine on its way to Yokohama and the money

already in his pocket. He'd come in out of the warm rain that sizzled

across the Ninsei pavement and somehow she'd been singled out for him,

one face out of the dozens who stood at the consoles, lost in the game she

played. The expression on her face, then, had been the one he'd seen,

hours later, on her sleeping face in a port side coffin, her upper lip like

the line children draw to represent a bird in flight.

Crossing the arcade to stand beside her, high on the deal he'd

made, he saw her glance up. Gray eyes rimmed with smudged black paintstick.

Eyes of some animal pinned in the headlights of an oncoming vehicle.

Their night together stretching into a morning, into tickets at the

hover port and his first trip across the Bay. The rain kept up, falling

along Harajuku, beading on her plastic jacket, the children of Tokyo

trooping past the famous boutiques in white loafers and cling wrap capes,

until she'd stood with him in the midnight clatter of a pachinko

parlor and held his hand like a child.

It took a month for the gestalt of drugs and tension he moved through

to turn those perpetually startled eyes into wells of reflexive need.

He'd watched her personality fragment, calving like an iceberg,

splinters drifting away, and finally he'd seen the raw need, the

hungry armature of addiction. He'd watched her track the next hit with

a concentration that reminded him of the mantises they sold in stalls along

Shiga, beside tanks of blue mutant carp and crickets caged in bamboo.

He stared at the black ring of grounds in his empty cup. It was

vibrating with the speed he'd taken. The brown laminate of the table

top was dull with a patina of tiny scratches. With the dex mounting through

his spine he saw the countless random impacts required to create a surface

like that. The Jarre was decorated in a dated, nameless style from the

previous century, an uneasy blend of Japanese traditional and pale Milanese

plastics, but everything seemed to wear a subtle film, as though the bad

nerves of a million customers had somehow attacked the mirrors and the once

glossy plastics, leaving each surface fogged with something that could never

be wiped away.

"Hey. Case, good buddy. . ."

He looked up, met gray eyes ringed with paintstick. She was wearing

faded French orbital fatigues and new white sneakers.

"I been lookin' for you, man." She took a seat opposite him, her

elbows on the table. The sleeves of the blue zip suit had been ripped out at

the shoulders; he automatically checked her arms for signs of derms or the

needle. "Want a cigarette?"

She dug a crumpled pack of Yeheyuan filters from an ankle pocket and

offered him one. He took it, let her light it with a red plastic tube. "You

sleepin' okay, Case? You look tired." Her accent put her south along

the Sprawl, toward Atlanta. The skin below her eyes was pale and

unhealthy-looking, but the flesh was still smooth and firm. She was twenty.

New lines of pain were starting to etch themselves permanently at the

corners of her mouth. Her dark hair was drawn back, held by a band of

printed silk. The pattern might have represented microcircuits, or a city

map.

"Not if I remember to take my pills," he said, as a tangible wave of

longing hit him, lust and loneliness riding in on the wavelength of

amphetamine. He remembered the smell of her skin in the overheated darkness

of a coffin near the port, her locked across the small of his back.

All the meat, he thought, and all it wants.

"Wage," she said, narrowing her eyes. "He wants to see you with a hole

in your face." She lit her own cigarette.

"Who says? Ratz? You been talking to Ratz?"

"No. Mona. Her new squeeze is one of Wage's boys."

"I don't owe him enough. He does me, he's out the money

anyway." He shrugged.

"Too many people owe him now, Case. Maybe you get to be the example.

You seriously better watch it."

"Sure. How about you, Linda? You got anywhere to sleep?"

"Sleep." She shook her head. "Sure, Case." She shivered, hunched

forward over the table. Her face was filmed with sweat.

"Here," he said, and dug in the pocket of his windbreaker, coming up

with a crumpled fifty. He smoothed it automatically, under the table, folded

it in quarters, and passed it to her.

"You need that, honey. You better give it to Wage." There was something

in the gray eyes now that he couldn't read, something he'd never

seen there before.

"I owe Wage a lot more than that. Take it. I got more coming," he lied,

as he watched his New Yen vanish into a zippered pocket.

"You get your money, Case, you find Wage quick."

"I'll see you, Linda," he said, getting up.

"Sure." A millimeter of white showed beneath each of her pupils.

Sanpaku. "You watch your back, man."

He nodded, anxious to be gone. He looked back as the plastic door swung

shut behind him, saw her eyes reflected in a cage of red neon.

Friday night on Ninsei.

He passed yakitori stands and massage parlors, a franchised coffee shop

called Beautiful Girl, the electronic thunder of an arcade. He stepped out

of the way to let a dark-suited sarariman by, spotting the

Mitsubishi-Genentech logo tattooed across the back of the man's right

hand.

Was it authentic? lf that's for real, he thought, he's in

for trouble. If it wasn't, served him right. M-G employees above a

certain level were implanted with advanced microprocessors that monitored

mutagen levels in the bloodstream. Gear like that would get you rolled in

Night City, rolled straight into a black clinic.

The sarariman had been Japanese, but the Ninsei crowd was a gaijin

crowd. Groups of sailors up from the port, tense solitary tourists hunting

pleasures no guidebook listed, Sprawl heavies showing off grafts and

implants, and a dozen distinct species of hustler, all swarming the street

in an intricate dance of desire and commerce.

There were countless theories explaining why Chiba City tolerated the

Ninsei enclave, but Case tended toward the idea that the Yakuza might be

preserving the place as a kind of historical park, a reminder of humble

origins. But he also saw a certain sense in the notion that burgeoning

technologies require outlaw zones, that Night City wasn't there for

its inhabitants, but as a deliberately unsupervised playground for

technology itself.

Was Linda right, he wondered, staring up at the lights? Would Wage have

him killed to make an example? It didn't make much sense, but then

Wage dealt primarily in proscribed biologicals, and they said you had to be

crazy to do that.

But Linda said Wage wanted him dead. Case's primary insight into

the dynamics of street dealing was that neither the buyer nor the seller

really needed him. A middleman's business is to make himself a

necessary evil. The dubious niche Case had carved for himself in the

criminal ecology of Night City had beep cut out with lies, scooped out a

night at a time with betrayal. Now, sensing that its walls were starting to

crumble, he felt the edge of a strange euphoria.

The week before, he'd delayed transfer of a synthetic glandular

extract, retailing it for a wider margin than usual. He knew Wage

hadn't liked that. Wage was his primary supplier, nine years in Chiba

and one of the few gaijin dealers who'd managed to forge links with

the rigidly stratified criminal establishment beyond Night City's

borders. Genetic materials and hormones trickled down to Ninsei along an

intricate ladder of fronts and blinds. Somehow Wage had managed to trace

something back, once, and now he enjoyed steady connections in a dozen

cities.

Case found himself staring through a shop window. The place sold small

bright objects to the sailors. Watches, flicknives, lighters, pocket VTRs,

Simstim decks, weighted manriki chains, and shuriken. The shuriken had

always fascinated him, steel stars with knife-sharp points. Some were

chromed, others black, others treated with a rainbow surface like oil on

water. But the chrome stars held his gaze. They were mounted against scarlet

ultra suede with nearly invisible loops of nylon fish line, their centers

stamped with dragons or yin yang symbols. They caught the street's

neon and twisted it, and it came to Case that these were the stars under

which he voyaged, his destiny spelled out in a constellation of cheap

chrome.

"Julie," he said to his stars. "Time to see old Julie. He'll

know."

Julius Deane was one hundred and thirty-five years old, his metabolism

assiduously warped by a weekly fortune in serums and hormones. His primary

hedge against aging was a yearly pilgrimage to Tokyo, where genetic surgeons

re-set the code of his DNA, a procedure unavailable in Chiba. Then

he'd fly to Hongkong and order the year's suits and shirts.

Sexless and inhumanly patient, his primary gratification seemed to lie in

his devotion to esoteric forms of tailor-worship. Case had never seen him

wear the same suit twice, although his wardrobe seemed to consist entirely

of meticulous reconstructions of garments of the previous century. He

affected prescription lenses, framed in spidery gold, ground from thin slabs

of pink synthetic quartz and beveled like the mirrors in a Victorian doll

house.

His offices were located in a warehouse behind Ninsei, part of which

seemed to have been sparsely decorated, years before, with a random

collection of European furniture, as though Deane had once intended to use

the place as his home. NeoAztec bookcases gathered dust against one wall of

the room where Case waited. A pair of bulbous Disney-styled table lamps

perched awkwardly on a low Kandinsky-look coffee table in scarlet-lacquered

steel. A Dali clock hung on the wall between the bookcases, its distorted

face sagging to the bare concrete floor. Its hands were holograms that

altered to match the convolutions of the face as they rotated, but it never

told the correct time. The room was stacked with white fiberglass shipping

modules that gave off the tang of preserved ginger.

"You seem to be clean, old son," said Deane's disembodied voice.

"Do come in." Magnetic bolts thudded out of position around the massive

imitation-rosewood door to the left of the bookcases. JULIUS DEANE IMPORT

EXPORT was lettered across the plastic in peeling self-adhesive capitals. If

the furniture scattered in Deane's makeshift foyer suggested the end

of the past century, the office itself seemed to belong to its start.

Deane's seamless pink face regarded Case from a pool of light

cast by an ancient brass lamp with a rectangular shade of dark green glass.

The importer was securely fenced behind a vast desk of painted steel,

flanked on either side by tall, drawered cabinets made of some sort of pale

wood. The sort of thing, Case supposed, that had once been used to store

written records of some kind. The desktop was littered with cassettes,

scrolls of yellowed printout, and various parts of some sort of clockwork

typewriter, a machine Deane never seemed to get around to reassembling.

"What brings you around, boyo?" Deane asked, offering Case a narrow

bonbon wrapped in blue-and-white checked paper. "Try one. Ting Ting Djahe,

the very best." Case refused the ginger, took a seat in a yawing wooden

swivel chair, and ran a thumb down the faded seam of one black jeans-leg.

"Julie I hear Wage wants to kill me."

"Ah. Well then. And where did you hear this, if I may?"

"People."

"People," Deane said, around a ginger bonbon. "What sort of people?

Friends?"

Case nodded.

"Not always that easy to know who your friends are, is it?"

"I do owe him a little money, Deane. He say anything to you?"

"Haven't been in touch, of late." Then he sighed. "If I did know,

of course, I might not be in a position to tell you. Things being what they

are, you understand."

"Things?"

"He's an important connection Case."

"Yeah. He want to kill me, Julie?"

"Not that I know of." Deane shrugged. They might have been discussing

the price of ginger. "If it proves to be an unfounded rumor, old son, you

come back in a week or so and I'll let you in on a little something

out of Singapore."

"Out of the Nan Hai Hotel, Bencoolen Street?"

"Loose lips, old son!" Deane grinned. The steel desk was jammed with a

fortune in debugging gear.

"Be seeing you, Julie. I'll say hello to Wage."

Deane's fingers came up to brush the perfect knot in his pale

silk tie.

He was less than a block from Deane's office when it hit, the

sudden cellular awareness that someone was on his ass, and very close.

The cultivation of a certain tame paranoia was something Case took for

granted. The trick lay in not letting it get out of control. But that could

be quite a trick, behind a stack of octagons. He fought the adrenaline surge

and composed his narrow features in a mask of bored vacancy, pretending to

let the crowd carry him along. When he saw a darkened display window, he

managed to pause by it. The place was a surgical boutique, closed for

renovations. With his hands in the pockets of his jacket, he stared through

the glass at a flat lozenge of vat grown flesh that lay on a carved pedestal

of imitation jade. The color of its skin reminded him of Zone's

whores; it was tattooed with a luminous digital display wired to a

subcutaneous chip. Why bother with the surgery, he found himself thinking,

while sweat coursed down his ribs, when you could just carry the thing

around in your pocket?

Without moving his head, he raised his eyes and studied the reflection

of the passing crowd.

There.

Behind sailors in short-sleeved khaki. Dark hair, mirrored glasses,

dark clothing, slender. . .

And gone.

Then Case was running, bent low, dodging between bodies.

"Rent me a gun, Shin?"

The boy smiled. "Two hour." They stood together in the smell of fresh

raw seafood at the rear of a Shiga sushi stall. "You come back, two hour."

"I need one now, man. Got anything right now?"

Shin rummaged behind empty two-liter cans that had once been filled

with powdered horseradish. He produced a slender package wrapped in gray

plastic. "Taser. One hour, twenty New Yen. Thirty deposit."

"Shit. I don't need that. I need a gun. Like I maybe wanna shoot

somebody, understand?"

The waiter shrugged, replacing the taser behind the horseradish cans.

"Two hour."

He went into the shop without bothering to glance at the display of

shuriken. He'd never thrown one in his life.

He bought two packs of Yeheyuans with a Mitsubishi Bank chip that gave

his name as Charles Derek May. It beat Truman Starr, the best he'd

been able to do for a passport.

The Japanese woman behind the terminal looked like she had a few years

on old Deane, none of them with the benefit of science. He took his slender

roll of New Yen out of his pocket and showed it to her. "I want to buy a

weapon."

She gestured in the direction of a case filled with knives.

"No," he said, "I don't like knives."

She brought an oblong box from beneath the counter. The lid was yellow

cardboard, stamped with a crude image of a coiled cobra with a swollen hood.

Inside were eight identical tissue-wrapped cylinders. He watched while

mottled brown fingers stripped the paper from one. She held the thing up for

him to examine, a dull steel tube with a leather thong at one end and a

small bronze pyramid at the other. She gripped the tube with one hand, the

pyramid between her other thumb and forefinger, and pulled. Three oiled,

telescoping segments of tightly wound coil spring slid out and locked.

"Cobra," she said.

Beyond the neon shudder of Ninsei, the sky was that mean shade of gray.

The air had gotten worse; it seemed to have teeth tonight, and half the

crowd wore filtration masks. Case had spent ten minutes in a urinal, trying

to discover a convenient way to conceal his cobra; finally he'd

settled for tucking the handle into the waistband of his jeans, with the

tube slanting across his stomach. The pyramidal striking tip rode between

his ribcage and the lining of his windbreaker. The thing felt like it might

clatter to the pavement with his next step, but it made him feel better.

The Chat wasn't really a dealing bar, but on weeknights it

attracted a related clientele. Fridays and Saturdays were different. The

regulars were still there, most of them, but they faded behind an influx of

sailors and the specialists who preyed on diem. As Case pushed through the

doors, he looked for Ratz, but the bartender wasn't in sight. Lonny

Zone, the bar's resident pimp, was observing with glazed fatherly

interest as one of his girls went to work on a young sailor. Zone was

addicted to a brand of hypnotic the Japanese called Cloud Dancers. Catching

the pimp's eye, Case beckoned him to the bar. Zone came drifting

through the crowd in slow motion, his long face slack and placid.

"You seen Wage tonight, Lonny?"

Zone regarded him with his usual calm. He shook his head.

"You sure, man?"

"Maybe in the Namban. Maybe two hours ago."

"Got some Joeboys with him? One of 'em thin, dark hair, maybe a

black jacket?"

"No," Zone said at last, his smooth forehead creased to indicate the

effort it cost him to recall so much pointless detail. "Big boys. Graftees."

Zone's eyes showed very little white and less iris; under the drooping

lids, his pupils were dilated and enormous. He stared into Case's face

for a long time, then lowered his gaze. He saw the bulge of the steel whip.

"Cobra," he said, and raised an eyebrow. "You wanna fuck somebody up?"

"See you, Lonny." Case left the bar.

His tail was back. He was sure of it. He felt a stab of elation the

octagons and adrenaline mingling with something else. You're enjoying

this, he thought; you're crazy.

Because, in some weird and very approximate way, it was like a run in

the matrix. Get just wasted enough, find yourself in some desperate but

strangely arbitrary kind of trouble, and it was possible to see Ninsei as a

field of data, the way the matrix had once reminded him of proteins linking

to distinguish cell specialties. Then you could throw yourself into a

highspeed drift and skid, totally engaged but set apart from it all, and all

around you the dance of biz, information interacting, data made flesh in the

mazes of the black market. . .

Go it, Case, he told himself. Suck 'em in. Last thing

they'll expect. He was half a block from the games arcade where

he'd first met Linda Lee.

He bolted across Ninsei, scattering a pack of strolling sailors. One of

them screamed after him in Spanish. Then he was through the entrance, the

sound crashing over him like surf, subsonics throbbing in the pit of his

stomach. Someone scored a ten-megaton hit on Tank War Europa, a simulated

air burst drowning the arcade in white sound as a lurid hologram fireball

mushroomed overhead. He cut to the right and loped up a flight of unpainted

chip board stairs. He'd come here once with Wage, to discuss a deal in

proscribed hormonal triggers with a man called Matsuga. He remembered the

hallway, its stained matting, the row of identical doors leading to tiny

office cubicles. One door was open now. A Japanese girl in a sleeveless

black t-shirt glanced up from a white terminal, behind her head a travel

poster of Greece, Aegian blue splashed with streamlined ideograms.

"Get your security up here," Case told her.

Then he sprinted down the corridor, out of her sight. The last two

doors were closed and, he assumed, locked. He spun and slammed the sole of

his nylon running shoe into the blue-lacquered composition door at the far

end. It popped, cheap hardware falling from the splintered frame. Darkness

there, the white curve of a terminal housing. Then he was on the door to its

right, both hands around the transparent plastic knob, leaning in with

everything he had. Something snapped, and he was inside. This was where he

and Wage had met with Matsuga, but whatever front company Matsuga had

operated was long gone. No terminal, nothing. Light from the alley behind

the arcade, filtering in through soot blown plastic. He made out a snake

like loop of fiber optics protruding from a wall socket, a pile of discarded

food containers, and the bladeless nacelle of an electric fan.

The window was a single pane of cheap plastic. He shrugged out of his

jacket, bundled it around his right hand, and punched. It split, requiring

two more blows to free it from the frame. Over the muted chaos of the games,

an alarm began to cycle, triggered either by the broken window or by the

girl at the head of the corridor.

Case turned, pulled his jacket on, and flicked the cobra to full

extension.

With the door closed, he was counting on his tail to assume he'd

gone through the one he'd kicked half off its hinges. The

cobra's bronze pyramid began to bob gently, the spring-steel shaft

amplifying his pulse.

Nothing happened. There was only the surging of the alarm, the crashing

of the games, his heart hammering. When the fear came, it was like some

half-forgotten friend. Not the cold rapid mechanism of the dex-paranoia, but

simple animal fear. He'd lived for so long on a constant edge of

anxiety that he'd almost forgotten what real fear was.

This cubicle was the sort of place where people died. He might die

here. They might have guns. . .

A crash, from the far end of the corridor. A man's voice,

shouting something in Japanese. A scream, shrill terror. Another crash.

And footsteps, unhurried, coming closer.

Passing his closed door. Pausing for the space of three rapid beats of

his heart. And returning. One, two, three. A bootheel scraped the matting.

The last of his octagon-induced bravado collapsed. He snapped the cobra

into its handle and scrambled for the window, blind with fear, his nerves

screaming. He was up, out, and falling, all before he was conscious of what

he'd done. The impact with pavement drove dull rods of pain through

his shins.

A narrow wedge of light from a half-open service hatch framed a heap of

discarded fiber optics and the chassis of a junked console. He'd

fallen face forward on a slab of soggy chip board, he rolled over, into the

shadow of the console. The cubicle's window was a square of faint

light. The alarm still oscillated, louder here, the rear wall dulling the

roar of the games.

A head appeared, framed in the window, back lit by the fluorescents in

the corridor, then vanished. It returned, but he still couldn't read

the features. Glint of silver across the eyes. "Shit," someone said, a

woman, in the accent of the northern Sprawl.

The head was gone. Case lay under the console for a long count of

twenty, then stood up. The steel cobra was still in his hand, and it took

him a few seconds to remember what it was. He limped away down the alley,

nursing his left ankle.

Shin's pistol was a fifty-year-old Vietnamese imitation of a

South American copy of a Walther PPK, double-action on the first shot, with

a very rough pull. It was chambered for .22 long rifle, and Case

would've preferred lead azide explosives to the simple Chinese hollow

points Shin had sold him. Still it was a handgun and nine rounds of

ammunition, and as he made his way down Shiga from the sushi stall he

cradled it in his jacket pocket. The grips were bright red plastic molded in

a raised dragon motif, something to run your thumb across in the dark.

He'd consigned the cobra to a dump canister on Ninsei and

dry-swallowed another octagon.

The pill lit his circuits and he rode the rush down Shiga to Ninsei,

then over to Baiitsu. His tail, he'd decided, was gone and that was

fine. He had calls to make, biz to transact, and it wouldn't wait. A

block down Baiitsu, toward the port, stood a featureless ten-story office

building in ugly yellow brick. Its windows were dark now, but a faint glow

from the roof was visible if you craned your neck. An unlit neon sign near

the main entrance offered CHEAP HOTEL under a cluster of ideograms. If the

place had another name, Case didn't know it; it was always referred to

as Cheap Hotel. You reached it through an alley off Baiitsu, where an

elevator waited at the foot of a transparent shaft. The elevator, like Cheap

Hotel, was an afterthought, lashed to the building with bamboo and epoxy.

Case climbed into the plastic cage and used his key, an unmarked length of

rigid magnetic tape.

Case had rented a coffin here, on a weekly basis, since he'd

arrived in Chiba, but he'd never slept in Cheap Hotel. He slept in

cheaper places.

The elevator smelled of perfume and cigarettes; the sides of the cage

was scratched and thumb-smudged. As it passed the fifth floor, he saw the

lights of Ninsei. He drummed his fingers against the pistol grip as the cage

slowed with a gradual hiss. As always, it came to a full stop with a violent

jolt, but he was ready for it. He stepped out into the courtyard that served

the place as some combination of lobby and lawn.

Centered in the square carpet of green plastic turf, a Japanese

teenager sat behind a C-shaped console, reading a textbook. The white

fiberglass coffins were racked in a framework of industrial scaffolding. Six

tiers of coffins, ten coffins on a side. Case nodded in the boy's

direction and limped across the plastic grass to the nearest ladder. The

compound was roofed with cheap laminated matting that rattled in a strong

wind and leaked when it rained, but the coffins were reasonably difficult to

open without a key.

The expansion-grate catwalk vibrated with his weight as he edged his

way along the third tier to Number 92. The coffins were three meters long,

the oval hatches a meter wide and just under a meter and a half tall. He fed

his key into the slot and waited for verification from the house computer.

Magnetic bolts thudded reassuringly and the hatch rose vertically with a

creak of springs. Fluorescents flickered on as he crawled in, pulling the

hatch shut behind him and slapping the panel that activated the manual

latch.

There was nothing in Number 92 but a standard Hitachi pocket computer

and a small white styrofoam cooler chest. The cooler contained the remains

of three ten-kilo slabs of dry ice carefully wrapped in paper to delay

evaporation, and a spun aluminum lab flask. Crouching on the brown

temperfoam slab that was both floor and bed, Case took Shin's .22 from

his pocket and put it on top of the cooler. Then he took off his jacket. The

coffin's terminal was molded into one concave wall, opposite a panel

listing house rules in seven languages. Case took the pink handset from its

cradle and punched a Hongkong number from memory. He let it ring five times,

then hung up. His buyer for the three megabytes of hot RAM in the Hitachi

wasn't taking calls.

He punched a Tokyo number in Shinjuku.

A woman answered, something in Japanese.

"Snake Man there?"

"Very good to hear from you," said Snake Man, coming in on an

extension. "I've been expecting your call."

"I got the music you wanted." Glancing at the cooler.

"I'm very glad to hear that. We have a cash flow problem. Can you

front?"

"Oh, man, I really need the money bad. . ."

Snake Man hung up.

"You shit" Case said to the humming receiver. He stared at the cheap

little pistol.

"Iffy," he said, "it's all looking very iffy tonight."

Case walked into the Chat an hour before dawn, both hands in the

pockets of his jacket; one held the rented pistol, the other the aluminum

flask.

Ratz was at a rear table, drinking Apollonaris water from a beer

pitcher, his hundred and twenty kilos of doughy flesh tilted against the

wall on a creaking chair. A Brazilian kid called Kurt was on the bar,

tending a thin crowd of mostly silent drunks. Ratz's plastic arm

buzzed as he raised the pitcher and drank. His shaven head was filmed with

sweat. "You look bad, friend artiste," he said, flashing the wet ruin of his

teeth.

"I'm doing just fine," said Case, and grinned like a skull.

"Super fine." He sagged into the chair opposite Ratz, hands still in his

pockets.

"And you wander back and forth in this portable bombshelter built of

booze and ups, sure. Proof against the grosser emotions, yes?"

"Why don't you get off my case, Ratz? You seen Wage?"

"Proof against fear and being alone," the bartender continued. "Listen

to the fear. Maybe it's your friend."

"You hear anything about a fight in the arcade tonight, Ratz? Somebody

hurt?"

"Crazy cut a security man." He shrugged. "A girl, they say."

"I gotta talk to Wage, Ratz, I. . ."

"Ah." Ratz's mouth narrowed, compressed into a single line. He

was looking past Case, toward the entrance. "I think you are about to."

Case had a sudden flash of the shuriken in their window. The speed sang

in his head. The pistol in his hand was slippery with sweat.

"Herr Wage," Ratz said, slowly extending his pink manipulator as if he

expected it to be shaken. "How great a pleasure. Too seldom do you honor

us."

Case turned his head and looked up into Wage's face. It was a

tanned and forgettable mask. The eyes were vat grown sea-green Nikon

transplants. Wage wore a suit of gunmetal silk and a simple bracelet of

platinum on either wrist. He was flanked by his Joe boys, nearly identical

young men, their arms and shoulders bulging with grafted muscle.

"How you doing, Case?"

"Gentlemen," said Ratz, picking up the table's heaped ashtray in

his pink plastic claw, "I want no trouble here." The ashtray was made of

thick, shatterproof plastic, and advertised Tsingtao beer. Ratz crushed it

smoothly, butts and shards of green plastic cascading onto the table top.

"You understand?"

"Hey, sweetheart," said one of the Joe boys, "you wanna try that thing

on me?"

"Don't bother aiming for the legs, Kurt," Ratz said, his tone

conversational. Case glanced across the room and saw the Brazilian standing

on the bar, aiming a Smith & Wesson riot gun at the trio. The

thing's barrel, made of paper-thin alloy wrapped with a kilometer of

glass filament, was wide enough to swallow a fist. The skeletal magazine

revealed five fat orange cartridges, subsonic sandbag jellies.

"Technically nonlethal," said Ratz.

"Hey, Ratz," Case said, "I owe you one."

The bartender shrugged. "Nothing, you owe me. These," and he glowered

at Wage and the Joe boys, "should know better. You don't take anybody

off in the Chatsubo."

Wage coughed. "So who's talking about taking anybody off? We just

wanna talk business. Case and me, we work together."

Case pulled the .22 out of his pocket and levelled it at Wage's

crotch. "I hear you wanna do me." Ratz's pink claw closed around the

pistol and Case let his hand go limp.

"Look, Case, you tell me what the fuck is going on with you, you wig or

something? What's this shit I'm trying to kill you?" Wage turned

to the boy on his left. "You two go back to the Namban. Wait for me."

Case watched as they crossed the bar, which was now entirely deserted

except for Kurt and a drunken sailor in khakis, who was curled at the foot

of a barstool. The barrel of the Smith & Wesson tracked the two to the

door, then swung back to cover Wage. The magazine of Case's pistol

clattered on the table. Ratz held the gun in his claw and pumped the round

out of the chamber.

"Who told you I was going to hit you, Case?" Wage asked.

Linda.

"Who told you, man? Somebody trying to set you up?"

The sailor moaned and vomited explosively.

"Get him out of here," Ratz called to Kurt, who was sitting on the edge

of the bar now, the Smith & Wesson across his lap, lighting a cigarette.

Case felt the weight of the night come down on him like a bag of wet

sand settling behind his eyes. He took the flask out of his pocket and

handed it to Wage. "All I got. Pituitaries. Get you five hundred if you move

it fast. Had the rest of my roll in some RAM, but that's gone by now."

"You okay, Case?" The flask had already vanished behind a gunmetal

lapel. "I mean, fine, this'll square us, but you look bad. Like

hammered shit. You better go somewhere and sleep."

"Yeah." He stood up and felt the Chat sway around him. "Well, I had

this fifty, but I gave it to somebody." He giggled. He picked up the

.22's magazine and the one loose cartridge and dropped them into one

pocket, then put the pistol in the other. "I gotta see Shin, get my deposit

back."

"Go home," said Ratz, shifting on the creaking chair with something

like embarrassment. "Artiste. Go home."

He felt them watching as he crossed the room and shouldered his way

past the plastic doors.

"Bitch," he said to the rose tint over Shiga. Down on Ninsei the

holograms were vanishing like ghosts, and most of the neon was already cold

and dead. He sipped thick black coffee from a street vendor's foam

thimble and watched the sun come up. "You fly away, honey. Towns like this

are for people who like the way down." But that wasn't it, really, and

he was finding it increasingly hard to maintain the sense of betrayal. She

just wanted a ticket home, and the RAM in his Hitachi would buy it for her,

if she could find the right fence. And that business with the fifty;

she'd almost turned it down, knowing she was about to rip him for the

rest of what he had.

When he climbed out of the elevator, the same boy was on the desk.

Different textbook. "Good buddy," Case called across the plastic turf, "you

don't need to tell me. I know already. Pretty lady came to visit, said

she had my key. Nice little tip for you, say fifty New ones?" The boy put

down his book. "Woman," Case said, and drew a line across his forehead with

his thumb. "Silk." He smiled broadly. The boy smiled back, nodded. "Thanks,

asshole," Case said.

On the catwalk, he had trouble with the lock. She'd messed it up

somehow when she'd fiddled it, he thought. Beginner. He knew where to

rent a black box that would open anything in Cheap Hotel. Fluorescents came

on as he crawled in.

"Close the hatch real slow, friend. You still got that Saturday night

special you rented from the waiter?"

She sat with her back to the wall, at the far end of the coffin. She

had her knees up, resting her wrists on them, the pepper box muzzle of a

flechette pistol emerged from her hands. "That you in the arcade?" He pulled

the hatch down. "Where's Linda?"

"Hit that latch switch."

He did.

"That your girl? Linda?"

He nodded.

"She's gone. Took your Hitachi. Real nervous kid. What about the

gun, man?" She wore mirrored glasses. Her clothes were black, the heels of

black boots deep in the temperfoam.

"I took it back to Shin, got my deposit. Sold his bullets back to him

for half what I paid. You want the money?"

"No."

"Want some dry ice? All I got, right now."

"What got into you tonight? Why'd you pull that scene at the

arcade? I had to mess up this rentacop came after me with nunchucks."

"Linda said you were gonna kill me."

"Linda said? I never saw her before I came up here."

"You aren't with Wage?"

She shook her head. He realized that the glasses were surgically inset,

sealing her sockets. The silver lenses seemed to grow from smooth pale skin

above her cheekbones, framed by dark hair cut in a rough shag. The fingers

curled around the fletcher were slender, white, tipped with polished

burgundy. The nails looked artificial. "I think you screwed up, Case. I

showed up and you just fit me right into your reality picture."

"So what do you want, lady?" He sagged back against the hatch.

"You. One live body, brains still somewhat intact. Molly, Case. My

name's Molly. I'm collecting you for the man I work for. Just

wants to talk, is all. Nobody wants to hurt you "

"That's good."

"'Cept I do hurt people sometimes, Case. I guess it's just

the way I'm wired." She wore tight black glove leather jeans and a

bulky black jacket cut from some matte fabric that seemed to absorb light.

"If I put this dart gun away, will you be easy, Case? You look like you like

to take stupid chances."

"Hey, I'm very easy. I'm a pushover, no problem."

"That's fine, man." The fletcher vanished into the black jacket.

"Because you try to fuck around with me, you'll be taking one of the

stupidest chances of your whole life."

She held out her hands, palms up, the white fingers slightly spread,

and with a barely audible click, ten double-edged, four-centimeter scalpel

blades slid from their housings beneath the burgundy nails.

She smiled. The blades slowly withdrew.

After a year of coffins, the room on the twenty-fifth floor of the

Chiba Hilton seemed enormous. It was ten meters by eight, half of a suite. A

white Braun coffee maker steamed on a low table by the sliding glass panels

that opened onto a narrow balcony.

"Get some coffee in you. Look like you need it." She took off her black

jacket, the fletcher hung beneath her arm in a black nylon shoulder rig. She

wore a sleeveless gray pullover with plain steel zips across each shoulder.

Bulletproof, Case decided, slopping coffee into a bright red mug. His arms

and legs felt like they were made out of wood.

"Case." He looked up, seeing the man for the first time. "My name is

Armitage." The dark robe was open to the waist, the broad chest hairless and

muscular, the stomach flat and hard. Blue eyes so pale they made Case think

of bleach. "Sun's up, Case. This is your lucky day, boy."

Case whipped his arm sideways and the man easily ducked the scalding

coffee. Brown stain running down the imitation rice paper wall. He saw the

angular gold ring through the left lobe. Special Forces. The man smiled.

"Get your coffee, Case," Molly said. "You're okay, but

you're not going anywhere 'til Armitage has his say." She sat

cross legged on a silk futon and began to fieldstrip the fletcher without

bothering to look at it. Twin mirrors tracking as he crossed to the table

and refilled his cup.

"Too young to remember the war, aren't you, Case?" Armitage ran a

large hand back through his cropped brown hair. A heavy gold bracelet

flashed on his wrist. "Leningrad, Kiev, Siberia. We invented you in Siberia,

Case."

"What's that supposed to mean?"

"Screaming Fist, Case. You've heard the name."

"Some kind of run, wasn't it? Tried to burn this Russian nexus

with virus programs. Yeah, I heard about it. And nobody got out."

He sensed abrupt tension. Armitagc walkcd to the window and looked out

over Tokyo Bay. "That isn't true. One unit made it back to Helsinki,

Case."

Case shrugged, sipped coffee.

"You're a console cowboy. The prototypes of the programs you use

to crack industrial banks were developed for Screaming Fist. For the assault

on the Kirensk computer nexus. Basic module was a Nightwing micro light, a

pilot, a matrix deck, a jockey. We were running a virus called Mole. The

Mole series was the first generation of real intrusion programs."

"Icebreakers," Case said, over the rim of the red mug.

"Ice from ICE, intrusion countermeasures electronics."

"Problem is, mister, I'm no jockey now, so I think I'll

just be going. . ."

"I was there, Case; I was there when they invented your kind."

"You got zip to do with me and my kind, buddy. You're rich enough

to hire expensive razor girls to haul my ass up here, is all. I'm

never gonna punch any deck again, not for you or anybody else." He crossed

to the window and looked down. "That's where I live now."

"Our profile says you're trying to con the street into killing

you when you're not looking."

"Profile?"

"We've built up a detailed model. Bought a go-to for each of your

aliases and ran the skim through some military software. You're

suicidal, Case. The model gives you a month on the outside. And our medical

projection says you'll need a new pancreas inside a year."

" 'We.&lsquo " He met the faded blue eyes. " ‘We'

who?"

"What would you say if I told you we could correct your neural damage,

Case?" Armitage suddenly looked to Case as if he were carved from a block of

metal; inert, enormously heavy. A statue. He knew now that this was a dream,

and that soon he'd wake. Armitage wouldn't speak again.

Case's dreams always ended in these freeze frames, and now this one

was over.

"What would you say, Case?"

Case looked out over the Bay and shivered.

"I'd say you were full of shit."

Armitage nodded.

"Then I'd ask what your terms were."

"Not very different than what you're used to, Case."

"Let the man get some sleep, Armitage," Molly said from her futon, the

components of the fletcher spread on the silk like some expensive puzzle.

"He's coming apart at the seams."

"Terms," Case said, "and now. Right now."

He was still shivering. He couldn't stop shivering.

The clinic was nameless, expensively appointed, a cluster of sleek

pavilions separated by small formal gardens. He remembered the place from

the round he'd made his first month in Chiba.

"Scared, Case. You're real scared." It was Sunday afternoon and

he stood with Molly in a sort of courtyard. White boulders, a stand of green

bamboo, black gravel raked into smooth waves. A gardener, a thing like a

large metal crab, was tending the bamboo.

"It'll work, Case. You got no idea, the kind of stuff Armitage

has. Like he's gonna pay these nerve boys for fixing you with the

program he's giving them to tell them how to do it. He'll put

them three years ahead of the competition. You got any idea what

that's worth?" She hooked thumbs in the belt loops of her leather

jeans and rocked backward on the lacquered heels of cherry red cowboy boots.

The narrow toes were sheathed in bright Mexican silver. The lenses were

empty quicksilver, regarding him with an insect calm.

"You're street samurai," he said. "How long you work for him?"

"Couple of months."

"What about before that?"

"For somebody else. Working girl, you know?"

He nodded.

"Funny, Case."

"What's funny?"

‘It's like I know you. That profile he's got. I know

how you're wired."

"You don't know me, sister."

"You're okay, Case. What got you, it's just called bad

luck."

"How about him? He okay, Molly?" The robot crab moved toward them,

picking its way over the waves of gravel. Its bronze carapace might have

been a thousand years old. When it was within a meter of her boots, it fired

a burst of light, then froze for an instant, analyzing data obtained.

"What I always think about first, Case, is my own sweet ass." The crab

had altered course to avoid her, but she kicked it with a smooth precision,

the silver boot-tip clanging on the carapace. The thing fell on its back,

but the bronze limbs soon righted it.

Case sat on one of the boulders, scuffing at the symmetry of the gravel

waves with the toes of his shoes. He began to search his pockets for

cigarettes. "In your shirt," she said.

"You want to answer my question?" He fished a wrinkled Yeheyuan from

the pack and she lit it for him with a thin slab of German steel that looked

as though it belonged on an operating table.

"Well, I'll tell you, the man's definitely on to something.

He's got big money now, and he's never had it before, and he

gets more all the time." Case noticed a certain tension around her mouth.

"Or maybe, maybe something's on to him. . ." She shrugged.

"What's that mean?"

"I don't know, exactly. I know I don't know who or what

we're really working for."

He stared at the twin mirrors. Leaving the Hilton, Saturday morning,

he'd gone back to Cheap Hotel and slept for ten hours . Then

he'd taken a long and pointless walk along the port's security

perimeter, watching the gulls turn circles beyond the chain link. If

she'd followed him, she'd done a good job of it. He'd

avoided Night City. He'd waited in the coffin for Armitage's

call. Now this quiet courtyard, Sunday afternoon, this girl with a

gymnast's body and conjurer's hands.

"If you'll come in now, sir, the anesthetist is waiting to meet

you." The technician bowed, turned, and reentered the clinic without waiting

to see if Case would follow.

Cold steel odor. Ice caressed his spine.

Lost, so small amid that dark, hands grown cold, body image fading down

corridors of television sky.

Voices.

Then black fire found the branching tributaries of the nerves, pain

beyond anything to which the name of pain is given. . .

Hold still. Don't move.

And Ratz was there, and Linda Lee, Wage and Lonny Zone, a hundred faces

from the neon forest, sailors and hustlers and whores, where the sky is

poisoned silver, beyond chain link and the prison of the skull.

Goddamn don't you move.

Where the sky faded from hissing static to the non color of the matrix,

and he glimpsed the shuriken, his stars.

"Stop it, Case, I gotta find your vein!" She was straddling his chest,

a blue plastic syrette in one hand. "You don't lie still, I'll

slit your fucking throat. You're still full of endorphin inhibitors."

He woke and found her stretched beside him in the dark.

His neck was brittle, made of twigs. There was a steady pulse of pain

midway down his spine. Images formed and reformed: a flickering montage of

the Sprawl's towers and ragged Fuller domes, dim figures moving toward

him in the shade beneath a bridge or overpass. . .

"Case? It's Wednesday, Case." She moved, rolling over, reaching

across him. A breast brushed his upper arm. He heard her tear the foil seal

from a bottle of water and drink. "Here." She put the bottle in his hand. "I

can see in the dark, Case. Micro channel image-amps in my glasses."

"My back hurts."

"That's where they replaced your fluid. Changed your blood too.

Blood 'cause you got a new pancreas thrown into the deal. And some new

tissue patched into your liver. The nerve stuff I dun no. Lot of injections.

They didn't have to open anything up for the main show." She settled

back beside him. "It's 2:43:12 AM, Case. Got a readout chipped into my

optic nerve."

He sat up and tried to sip from the bottle. Gagged, coughed, lukewarm

water spraying his chest and thighs.

"I gotta punch deck," he heard himself say. He was groping for his

clothes. "I gotta know. . ."

She laughed. Small strong hands gripped his upper arms. "Sorry,

hotshot. Eight day wait. Your nervous system would fall out on the floor if

you jacked in now. Doctor's orders. Besides, they figure it worked.

Check you in a day or so." He lay down again.

"Where are we?"

"Home. Cheap Hotel."

"Where's Armitage?"

"Hilton, selling beads to the natives or something. We're out of

here soon, man. Amsterdam, Paris, then back to the Sprawl." She touched his

shoulder. "Roll over. I give a good massage."

He lay on his stomach, arms stretched forward, tips of his fingers

against the walls of the coffin. She settled over the small of his back,

kneeling on the temperfoam, the leather jeans cool against his skin. Her

fingers brushed his neck.

"How come you're not at the Hilton?"

She answered him by reaching back, between his thighs and gently

encircling his scrotum with thumb and forefinger. She rocked there for a

minute in the dark, erect above him, her other hand on his neck. The leather

of her jeans creaked softly with the movement. Case shifted, feeling himself

harden against the temperfoam.

His head throbbed, but the brittleness in his neck seemed to retreat.

He raised himself on one elbow, rolled, sank back against the foam, pulling

her down, licking her breasts, small hard nipples sliding wet across his

cheek. He found the zip on the leather jeans and tugged it down.

"It's okay," she said, "I can see." Sound of the jeans peeling

down. She struggled beside him until she could kick them away. She threw a

leg across him and he touched her face. Unexpected hardness of the implanted

lenses. "Don't," she said, "fingerprints."

Now she straddled him again, took his hand, and closed it over her, his

thumb along the cleft of her buttocks, his fingers spread across the labia.

As she began to lower herself, the images came pulsing back, the faces,

fragments of neon arriving and receding. She slid down around him and his

back arched convulsively. She rode him that way, impaling herself, slipping

down on him again and again, until they both had come, his orgasm flaring

blue in a timeless space, a vastness like the matrix, where the faces were

shredded and blown away down hurricane corridors, and her inner thighs were

strong and wet against his hips.

On Nisei, a thinner, weekday version of the crowd went through the

motions of the dance. Waves of sound rolled from the arcades and pachinko

parlors. Case glanced into the Chat and saw Zone watching over his girls in

the warm, beer-smelling twilight. Ratz was tending bar.

"You seen Wage, Ratz?"

"Not tonight." Ratz made a point of raising an eyebrow at Molly.

"You see him, tell him I got his money."

"Luck changing, my artiste?"

"Too soon to tell."

"Well, I gotta see this guy," Case said, watching his reflection in her

glasses. "I got biz to cancel out of."

"Armitage won't like it, I let you out of my sight." She stood

beneath Deane's melting clock, hands on her hips.

"The guy won't talk to me if you're there. Deane I

don't give two shits about. He takes care of himself. But I got people

who'll just go under if I walk out of Chiba cold. It's my

people, you know?"

Her mouth hardened. She shook her head.

"I got people in Singapore, Tokyo connections in Shinjuku and Asakuza,

and they'll go down, understand?" he lied, his hand on the shoulder of

her black jacket. "Five. Five minutes. By your clock, okay?"

"Not what I'm paid for."

"What you're paid for is one thing. Me letting some tight friends

die because you're too literal about your instructions is something

else."

"Bullshit. Tight friends my ass. You're going in there to check

us out with your smuggler." She put a booted foot up on the dust-covered

Kandinsky coffee table.

"Ah, Case, sport, it does look as though your companion there is

definitely armed, aside from having a fair amount of silicon in her head .

What is this about, exactly?" Deane's ghostly cough seemed to hang in

the air between them.

"Hold on, Julie. Anyway, I'll be coming in alone."

"You can be sure of that, old son. Wouldn't have it any other

way."

"Okay," she said. "Go. But five Minutes. Any more and I'll come

in and cool your tight friend permanently. And while you're at it, you

try to figure something out."

"What's that?"

"Why I'm doing you the favor." She turned and walked out, past

the stacked white modules of preserved ginger.

"Keeping stranger company than usual, Case?" asked Julie.

"Julie, she's gone. You wanna let me in? Please, Julie?"

The bolts worked. "Slowly, Case," said the voice.

"Turn on the works, Julie, all the stuff in the desk," Case said,

taking his place in the swivel chair.

"It's on all the time," Deane said mildly, taking a gun from

behind the exposed works of his old mechanical typewriter and aiming it

carefully at Case. It was a belly gun, a magnum revolver with the barrel

sawn down to a nub. The front of the trigger-guard had been cut away and the

grips wrapped with what looked like old masking tape. Case thought it looked

very strange in Dean's manicured pink hands. "Just taking care, you

Understand. Nothing personal. Now tell me what you want."

"I need a history lesson, Julie. And a go-to on somebody."

"What's moving, old son?" Deane's shirt was candy-striped

cotton, the collar white and rigid, like porcelain.

"Me, Julie. I'm leaving. Gone. But do me the favor, okay?"

"Go-to on whom, old son?"

"Gaijin name of Armitage, suite in the Hilton."

Deane put the pistol down. "Sit still, Case." He tapped something out

on a lap terminal. "It seems as though you know as much as my net does,

Case. This gentleman seems to have a temporary arrangement with the Yakuza,

and the sons of the neon chrysanthemum have ways of screening their allies

from the likes of me. I wouldn't have it any other way. Now, history.

You said history." He picked up the gun again, but didn't point it

directly at Case.

"What sort of history?"

"The war. You in the war, Julie?"

"The war? What's there to know? Lasted three weeks."

"Screaming Fist."

"Famous. Don't they teach you history these days? Great bloody

postwar political football, that was. Watergated all to hell and back. Your

brass, Case, your Sprawlside brass in, where was it, McLean? In the bunkers,

all of that. . . great scandal. Wasted a fair bit of patriotic young flesh

in order to test some new technology. They knew about the Russians'

defenses, it came out later. Knew about the emps, magnetic pulse weapons.

Sent these fellows in regardless, just to see." Deane shrugged. "Turkey

shoot for Ivan."

"Any of those guys make it out?"

"Christ," Deane said, "it's been bloody years. . . Though I do

think a few did. One of the teams. Got hold of a Sov gunship. Helicopter,

you know. Flew it back to Finland. Didn't have entry codes, of course,

and shot hell out of the Finnish defense forces in the process. Special

Forces types." Deane sniffed. "Bloody hell."

Case nodded. The smell of preserved ginger was overwhelming.

"I spent the war in Lisbon, you know," Deane said, putting the gun

down. "Lovely place, Lisbon."

"In the service, Julie?"

"Hardly. Though I did see action." Deane smiled his pink smile.

"Wonderful what a war can do for one's markets."

"Thanks, Julie. I owe you one."

"Hardly, Case. And goodbye."

And later he'd tell himself that the evening at Sammi's had

felt wrong from the start, that even as he'd followed Molly along that

corridor, shuffling through a trampled mulch of ticket stubs and styrofoam

cups, he'd sensed it. Linda's death, waiting. . .

They'd gone to the Namban, after he'd seen Deane, and paid

off his debt to Wage with a roll of Armitage's New Yen. Wage had liked

that, his boys had liked it less, and Molly had grinned at Case's side

with a kind of ecstatic feral intensity, obviously longing for one of them

to make a move. Then he'd taken her back to the Chat for a drink.

"Wasting your time, cowboy," Molly said, when Case took an octagon from

the pocket of his jacket. "How's that? You want one?" He held the pill

out to her.

"Your new pancreas, Case, and those plugs in your liver. Armitage had

them designed to bypass that shit." She tapped the octagon with one burgundy

nail. "You're biochemically incapable of getting off on amphetamine or

cocaine."

"Shit," he said. He looked at the octagon, then at her.

"Eat it. Eat a dozen. Nothing'll happen."

He did. Nothing did.

Three beers later, she was asking Ratz about the fights.

"Sammi's," Ratz said. "I'll pass," Case said, "I hear they

kill each other down there."

An hour later, she was buying tickets from a skinny Thai in a white

t-shirt and baggy rugby shorts.

Sammi's was an inflated dome behind a port side warehouse, taut

gray fabric reinforced with a net of thin steel cables. The corridor, with a

door at either end, was a crude airlock preserving the pressure differential

that supported the dome. Fluorescent rings were screwed to the plywood

ceiling at intervals, but most of them had been broken. The air was damp and

close with the smell of sweat and concrete.

None of that prepared him for the arena, the crowd, the tense hush, the

towering puppets of light beneath the dome. Concrete sloped away in tiers to

a kind of central stage, a raised circle ringed with a glittering thicket of

projection gear. No light but the holograms that shifted and flickered above

the ring, reproducing the movements of the two men below. Strata of

cigarette smoke rose from the tiers, drifting until it struck currents set