mical bodies, as the train works its way past.

The cables catch Waterhouse's eye: neatly bracketed to the stone walls

in parallel courses. They are like the creepers of some plutonic ivy that

spreads through the darkness of the Tube when the maintenance men aren't

paying attention, seeking a place to break out and up into the light.

When you walk along the street, up there in the Overground, you see the

first tendrils making their way up the ancient walls of the buildings.

Neoprene jacketed vines that grow in straight lines up sheer stone and

masonry and inject themselves through holes in windowframes, homing in

particularly on offices. Sometimes they are sheathed in metal tubes.

Sometimes the owners have painted them over. But all of them share a common

root system that flourishes in the unused channels and crevices of the

Underground, converging on giant switching stations in deep bomb proof

vaults.

The train invades a cathedral of dingy yellow light, and groans to a

stop, hogging the aisle. Lurid icons of national paranoia glow in the niches

and grottoes. An angelic chin thrusting woman anchors one end of the moral

continuum. At the opposite we have a succubus in a tight skirt, sprawled on

a davenport in the midst of a party. smirking through her false eyelashes as

she eavesdrops on the naive young servicemen gabbing away behind her.

Signs on the wall identify this as Euston in a tasteful sans serif that

screams official credibility. Waterhouse and most of the other people get

off the train. After fifteen minutes or so of ricocheting around the

station's precincts, asking directions and puzzling out timetables,

Waterhouse finds himself sitting aboard an intercity train bound for

Birmingham. Along the way, it is promised, it will stop at a place called

Bletchley.

Part of the reason for the confusion is that there is another train

about to leave from an adjacent siding, which goes straight to Bletchley,

its final destination, with no stops in between. Everyone on that train, it

seems, is a female in a quasimilitary uniform.

The RAF men with the Sten guns, standing watch by each door of that

train, checking papers and passes, will not let him aboard. Waterhouse looks

through the yellowing influence of the windows at the Bletchley girls in the

train, facing each other in klatsches of four and five, getting their

knitting out of their bags, turning balls of Scottish wool into balaclavas

and mittens for convoy crews in the North Atlantic, writing letters to their

brothers in the service and their mums and dads at home. The RAF gunmen

remain by the doors until all of them are closed and the train has begun to

move out of the station. As it builds speed, the rows and rows of girls,

knitting and writing and chatting, blur together into something that

probably looks a good deal like what sailors and soldiers the world over are

commonly seeing in their dreams. Waterhouse will never be one of those

soldiers, out on the front line, out in contact with the enemy. He has

tasted the apple of forbidden knowledge. He is forbidden to go anywhere in

the world where he might be captured by the enemy.

***

The train climbs up out of the night and into a red brick arroyo,

headed northwards out of the city. It is about three in the afternoon; that

special BP train must have been carrying swing shift gals.

Waterhouse has the feeling he will not be working anything like a

regular shift. His duffel bag which was packed for him is pregnant with

sartorial possibilities: thick oiled wool sweaters, tropical weight Navy and

Army uniforms, black ski mask, condoms.

The train slowly pulls free of the city and passes into a territory

patched with small residential towns. Waterhouse feels heavy in his seat,

and suspects a slight uphill tendency. They pass through a cleft that has

been made across a low range of hills, like a kerf in the top of a log, and

enter into a lovely territory of subtly swelling emerald green fields strewn

randomly with small white capsules that he takes to be sheep.

Of course, their distribution is probably not random at all it probably

reflects local variations in soil chemistry producing grass that the sheep

find more or less desirable. From aerial reconnaissance, the Germans could

draw up a map of British soil chemistry based upon analysis of sheep

distribution.

The fields are enclosed by old hedges, stone fences, or, especially in

the uplands, long swaths of forest. After an hour or so, the forest comes

right up along the left side of the train, covering a bank that rises up

gently from the railway siding. The train's brakes come on gassily, and the

train grumbles to a stop in a whistle stop station. But the line has forked

and ramified quite a bit, more than is warranted by the size of the station.

Waterhouse stands, plants his feet squarely, squats down in a sumo

wrestler's stance, and engages his duffel bag. Duffel appears to be winning

as it seemingly pushes Waterhouse out the door of the train and onto the

platform.

There is a stronger than usual smell of coal, and a good deal of noise

coming from not far away. Waterhouse looks up the line and discovers a heavy

industrial works unfurled across the many sidings. He stands and stares for

a couple of minutes, as his train pulls away, headed for points north, and

sees that they are in the business of repairing steam locomotives here at

Bletchley Depot. Waterhouse likes trains.

But that is not why he got a free suit of clothes and a ticket to

Bletchley, and so once again Waterhouse engages Duffel and gets it up the

stairs to the enclosed bridge that flies over all of the parallel lines.

Looking toward the station, he sees more Bletchley girls, WAAFs and WRENs,

coming towards him; the day shift, finished with their work, which consists

of the processing of ostensibly random letters and digits on a heavy

industrial scale. Not wanting to appear ridiculous in their sight, he

finally gets Duffel maneuvered onto his back, gets his arms through the

shoulder straps, and allows its weight to throw him forward across the

bridge.

The WAAFs and WRENs are only moderately interested in the sight of a

newly arriving American officer. Or perhaps they are only being demure. In

any case, Waterhouse knows he is one of the few, but not the first. Duffel

shoves him through the one room station like a fat cop chivvying a

hammerlocked drunk across the lobby of a two star hotel. Waterhouse is

ejected into a strip of open territory running along the north south road.

Directly across from him the woods rise up. Any notion that they might be

woods of the inviting sort is quickly dissolved by a dense spray of gelid

light glinting from the border of the wood as the low sun betrays that the

place is saturated with sharpened metal. There is an orifice in the woods,

spewing WAAFs and WRENs like the narrow outlet of a giant yellowjacket nest.

Waterhouse must either move forward or be pulled onto his back by

Duffel and left squirming helplessly in the parking lot like a flipped

beetle, so he staggers forward, across the street and onto the wide footpath

into the woods. The Bletchley girls surround him. They have celebrated the

end of their shift by applying lipstick. Wartime lipstick is necessarily

cobbled together from whatever tailings and gristle were left over once all

of the good stuff was used to coat propeller shafts. A florid and cloying

scent is needed to conceal its unspeakable mineral and animal origins.

It is the smell of War.

Waterhouse has not even been given the full tour of BP yet, but he

knows the gist of it. He knows that these demure girls, obediently shuffling

reams of gibberish through their machines, shift after shift, day after day,

have killed more men than Napoleon.

He makes slow and apologetic progress against the tide of the departing

day shift. At one point he simply gives up, steps aside, body slams Duffel

into the ivy, lights up a cigarette, and waits for a burst of a hundred or

so girls to go by him. Something pokes at his ankle: a wild raspberry cane,

furious with thorns. It supports an uncannily small and tidy spider web

whose geodesic strands gleam in a beam of low afternoon light. The spider in

the center is an imperturbable British sort, perfectly unruffled by

Waterhouse's clumsy Yank antics.

Waterhouse reaches out and catches a yellow brown elm leaf that happens

to fall through the air before him. He hunkers down, plants his cigarette in

his mouth, and, using both hands for steadiness, draws the sawtooth rim of

the elm leaf across one of the web's radial strands, which, he knows, will

not have any sticky stuff on it. Like a fiddle bow on a string, the leaf

sets up a fairly regular vibration in the web. The spider spins to face it,

rotating instantly, like a character in a badly spliced movie. Waterhouse is

so startled by the speed of the move that he starts back just a bit, then he

draws the leaf across the web again. The spider tenses, feeling the

vibrations.

Eventually it returns to its original position and carries on as

before, ignoring Waterhouse completely.

Spiders can tell from the vibrations what sort of insect they have

caught, and home in on it. There is a reason why the webs are radial, and

the spider plants itself at the convergence of the radii. The strands are an

extension of its nervous system. Information propagates down the gossamer

and into the spider, where it is processed by some kind of internal Turing

machine. Waterhouse has tried many different tricks, but he has never been

able to spoof a spider. Not a good omen!

The rush hour seems to have ended during Waterhouse's science

experiment. He engages Duffel once more. The struggle takes them another

hundred yards down the path, which finally empties out into a road just at

the point where it is barred by an iron gate slung between stupid obelisks

of red brick. The guards are, again, RAF men with Sten guns, and right now

they are examining the papers of a man in a canvas greatcoat and goggles,

who has just ridden up on an Army green motorcycle with panniers slung over

the rear wheel. The panniers are not especially full, but they have been

carefully secured; they contain the ammunition that the girls feed into the

chattering teeth of their ravenous weapons.

The motorcyclist is waved through, and makes an immediate left turn

down a narrow lane. Attention falls upon Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse, who

after a suitable exchange of salutes, presents his credentials.

He has to choose among his several sets, which he doesn't manage to

hide from the guards. But the guards do not seem alarmed or even curious

about this, which sets them distinctly apart from most whom Waterhouse has

dealt with. Naturally, these men are not on the Ultra Mega list, and so it

would be a grave breach of security to tell them that he was here on Ultra

Mega business. They appear to have greeted many other men who can't state

their real business, however, and don't bat an eyelash when Lawrence

pretends to be one of the naval intelligence liaisons in Hut 4 or Hut 8.

Hut 8 is where they decrypt naval Enigma transmissions. Hut 4 accepts

the decrypts from Hut 8 and analyzes them. If Waterhouse pretends to be a

Hut 4 man the disguise will not last for long, because those fellows have to

actually know something about the Navy. He perfectly fits the profile of a

Hut 8 man, who need not know anything except pure math.

One of the RAF men peruses his papers, then steps into a small

guardhouse and stirs the crank on a telephone. Waterhouse stands there

awkwardly, marveling at the weapons slung from the shoulders of the RAP men.

They are, as far as he can tell, nothing more than steel pipes with a

trigger mounted toward one end. A small window cut through the pipe provides

a view of a coil spring nested inside. A few handles and fittings bolted on

from place to place do not make the Sten gun look any less like an ill

conceived high school metal shop project.

"Captain Waterhouse? You are to proceed to the Mansion," says the guard

who had spoken on the telephone. "You can't miss it."

Waterhouse walks for about fifty feet and finds that the Mansion is,

indeed, tragically unmissable. He stands and stares at it for a minute,

trying to fathom what the architect had been thinking. It is a busy piece of

work, with an excessive number of gables. He can only suppose that the

designer wanted to build what was really a large, single dwelling, but

sought to camouflage it as a line of at least half a dozen wildly mismatched

urban row houses inexplicably crammed together in the middle of six hundred

acres of Buckinghamshire farmland.

The place has been well looked after, but as Waterhouse draws closer,

he can see black lianas climbing up the brickwork. The root system that he

glimpsed in the Underground has spread beneath forest and pasture even to

this place and has begun to throw its neoprene creepers upwards. But this

organism is not phototropic it does not grow towards the light, always

questing towards the sun. It is infotropic. And it has spread to this place

for the same reason that infotropic humans like Lawrence Pritchard

Waterhouse and Dr. Alan Mathison Turing have come here, because Bletchley

Park has roughly the same situation in the info world as the sun does in the

solar system. Armies, nations, prime ministers, presidents and geniuses fall

around it, not in steady planetlike orbits but in the crazy careening

ellipses and hyperbolae of comets and stray asteroids.

Dr. Rudolf von Hacklheber can't see Bletchley Park, because it is the

second best kept secret in the world, after Ultra Mega. But from his office

in Berlin, sifting through dispatches from the Beobachtung Dienst, he can

glimpse fragments of those trajectories, and dream up hypotheses to explain

why they are just so. If the only logical hypothesis is that the Allies have

broken Enigma, then Detachment 2702 will have failed.

Lawrence displays further credentials and enters between a pair of

weathered gryphons. The mansion is nicer once you can no longer see its

exterior. Its faux rowhouse design provides many opportunities for bay

windows, providing sorely needed light. The hall is held up by gothic arches

and pillars made of a conspicuously low grade of brown marble that looks

like vitrified sewage.

The place is startlingly noisy; there is a rushing, clattering noise,

like rabid applause, permeating walls and doors, carried on a draft of hot

air with a stinging, oily scent. It is the peculiar scent of electric

teletypes or teleprinters, as the Brits call them. The noise and the heat

suggest there must be dozens of them in one of the mansion's lower rooms.

Waterhouse climbs a paneled stairway to what the Brits call the first

floor, and find it quieter and cooler. The high panjandrums of Bletchley

have their offices here. If the organization is run true to bureaucratic

form, Waterhouse will never see this place again once his initial interview

is finished. He finds his way to the office of Colonel Chattan, who

(Waterhouse's memory jogged by the sight of the name on the door) is the

fellow at the top of the chart of Detachment 2702.

Chattan rises to shake his hand. He's strawberry blond, blue eyed, and

probably would be rosy cheeked if he didn't have such a deep desert tan at

the moment. He is wearing a dress uniform; British officers have their

uniforms tailor made, it is the only way to obtain them. Waterhouse is

hardly a clothes horse, but he can see at a glance that Chattan's uniform

was not thrown together by Mummy in a few evenings in front of a flickering

coal grate. No, Chattan has himself an honest to god tailor somewhere. Yet,

when he speaks Waterhouse's name, he does not say "woe to hice" like the

Broadway Buildings crowd. The R comes through hard and crackling and the

"house" part is elongated into some thing like "hoos." He has some kind of a

wild ass accent on him, this Chattan.

With Chattan is a smaller man in British fatigues tight at the wrists

and ankles, otherwise blousy, of thick khaki flannel that would be

intolerably hot if these people couldn't rely on a steady ambient

temperature, indoors and out, of about fifty five degrees. The overall

effect always reminds Waterhouse of Dr. Dentons. This fellow is introduced

as Leftenant Robson, and he is the leader of one of 2702's two squads the

RAE one. He has a bristly mustache, trimmed very short, of silver and auburn

whiskers. He is a cheerful sort, at least in the presence of higher ranks,

and smiles frequently. His teeth splay out radially from the gumline so that

each mandible has the appearance of a coffee can in which a small grenade

has been detonated.

"This the fellow we've been waiting for," Chattan says to Robson. "The

one we could've used in Algiers."

"Yes!" Robson says. "Welcome to Detachment 2701, Captain Waterhouse."

"2702," Waterhouse says.

Chattan and Robson look ever so mildly startled.

"We can't use 2701 because it is the product of two primes."

"I beg your pardon?" Robson says.

One thing Waterhouse likes about these Brits is that when they don't

know what the hell you are talking about, they are at least open to the

possibility that it might be their fault. Robson has the look of a man who

has come up through the ranks. A Yank of that type would already be scornful

and blustery.

"Which ones?" Chattan says. That is encouraging; he at least knows what

a prime number is.

"73 and 37," Waterhouse says.

This makes a profound impression on Chattan. "Ah, yes, I see." He

shakes his head. "I shall have to give the Prof a good chaffing about this."

Robson has cocked his head far to one side so that it is almost resting

upon the thick woolly beret chucked into his epaulet. He is squinting, and

has an aghast look about him. His hypothetical Yank counterpart would

probably demand, at this point, a complete explanation of prime number

theory, and when it was finished, denounce it as horseshit. But Robson just

lets it go by. "Am I to understand that we are changing the number of our

Detachment?"

Waterhouse swallows. It seems clear from Robson's reaction that this is

going to involve a great deal of busy work for Robson and his men: weeks of

painting and stenciling and of trying to propagate the new number throughout

the military bureaucracy. It will be a miserable pain in the ass.

"2702 it is," Chattan says breezily. Unlike Waterhouse, he has no

difficulty issuing difficult, unpopular commands.

"Right then, I must see to some things. Pleasure making your

acquaintance, Captain Waterhouse."

"Pleasure's mine."

Robson shakes Waterhouse's hand again and excuses himself.

"We have a billet for you in one of the huts to the south of the

canteen," Chattan says. "Bletchley Park is our nominal headquarters, but we

anticipate that we will spend most of our time in those theaters where

heaviest use is being made of Ultra."

"I take it you've been in North Africa," Waterhouse says.

"Yes." Chattan raises his eyebrows, or rather the ridges of skin where

his eyebrows are presumably located; the hairs are colorless and

transparent, like nylon monofilament line. "Just got out by the skin of our

teeth there, I'm afraid."

"Had a close shave, did you?"

"Oh, I don't mean it that way," Chattan says. "I'm talking about the

integrity of the Ultra secret. We are still not sure whether we have

survived it. But the Prof has done some calculations suggesting that we may

be out of the woods."

"The Prof is what you call Dr. Turing?"

"Yes. He recommended you personally, you know."

"When the orders came through, I speculated as much."

"Turing is presently engaged on at least two other fronts of the

information war, and could not be part of our happy few."

"What happened in North Africa, Colonel Chattan?"

"It's still happening," Chattan says bemusedly. "Our Marine squad is

still in theater, widening the bell curve.

"Widening the bell curve?"

"Well, you know better than I do that random things typically have a

bell shaped distribution. Heights, for example. Come over to this window,

Captain Waterhouse."

Waterhouse joins Chattan at a bay window, where there is a view across

acres of what used to be gently undulating farmland. Looking beyond the

wooded belt to the uplands miles away, he can see what Bletchley Park

probably used to look like: green fields dotted with clusters of small

buildings.

But that is not what it looks like now. There is hardly a piece of land

within half a mile that has not been recently paved or built upon. Once you

get beyond the Mansion and its quaint little outbuildings, the park consists

of one story brick structures, nothing more than long corridors with

multiple transepts: +++++++, and new +'s being added as fast as the masons

can slap bricks on mud (Waterhouse wonders, idly, whether Rudy has seen

aerial reconnaissance photos of this place, and deduced from all of those

+'s the mathematical nature of the enterprise). The tortuous channels

between buildings are narrow, and each is made twice as narrow by an eight

foot high blast wall running down the middle of it, so that the Jerries will

have to spend at least one bomb for each building.

"In that building there," Chattan says, pointing to a small building

not far away a truly wretched looking brick hovel "are the Turing Bombes.

That's 'bombe' with an 'e' on the end. They are calculating machines

invented by your friend the Prof."

"Are they true universal Turing machines?" Waterhouse blurts. He is in

the grip of a stunning vision of what Bletchley Park might, in fact, be: a

secret kingdom in which Alan has somehow found the resources needed to

realize his great vision. A kingdom ruled not by men but by information,

where humble buildings made of + signs house Universal Machines that can be

configured to perform any computable operation.

"No," Chattan says, with a gentle, sad smile.

Waterhouse exhales for a long time. "Ah."

"Perhaps that will come next year, or the next."

"Perhaps."

"The bombes were adapted, by Turing and Welchman and others, from a

design dreamed up by Polish cryptanalysts. They consist of rotating drums

that test many possible Enigma keys with great speed. I'm sure the Prof will

explain it to you. But the point is that they have these vast pegboards in

the back, like telephone switchboards, and some of our girls have the job of

putting the right pegs into the right holes and wiring the things up every

day. Requires good eyesight, careful attention, and height."

"Height?"

"You'll notice that the girls who are assigned to that particular duty

are unusually tall. If the Germans were to somehow get their hands on the

personnel records for all of the people who work at Bletchley Park, and

graph their heights on a histogram, they would see a normal bell shaped

curve, representing most of the workers, with an abnormal bump on it

representing the unusual population of tall girls whom we have brought in to

work the plug boards."

"Yes, I see," Waterhouse says, "and someone like Rudy Dr. von

Hacklheber would notice the anomaly, and wonder about it."

"Precisely," Chattan says. "And it would then be the job of Detachment

2702 the Ultra Mega Group to plant false information that would throw your

friend Rudy off the scent." Chattan turns away from the window, strolls over

to his desk, and opens a large cigarette box, neatly stacked with fresh

ammunition. He offers one to Waterhouse with a deft hand gesture, and

Waterhouse accepts it, just to be social. As Chattan is giving him a light,

he gazes through the flame into Waterhouse's eye and says, 'I put it to you

now. How would you go about concealing from your friend Rudy that we had a

lot of tall girls here?'

"Assuming that he already had the personnel records?"

"Yes."

"Then it would be too late to conceal anything."

"Granted. Let us instead assume that he has some channel of information

that is bringing him these records, a few at a time. This channel is still

open and functioning. We cannot shut it down. Or perhaps we choose not to

shut it down, because even the absence of this channel will tell Rudy

something important."

"Well, there you go then," Waterhouse says. "We gin up some false

personnel records and plant them in the channel."

There is a small chalkboard on the wall of Chattan's office. It is a

palimpsest, not very well erased; the housekeeping detail here must have a

standing order never to clean it, lest something important be lost. As

Waterhouse approaches it, he can see older calculations layered atop each

other, fading off into the blackness like transmissions of white light

propagating into deep space.

He recognizes Alan's handwriting all over the place. It takes a

physical effort not to stand there and try to reconstruct Alan's

calculations from the ghosts lingering on the slate. He draws over them only

with reluctance.

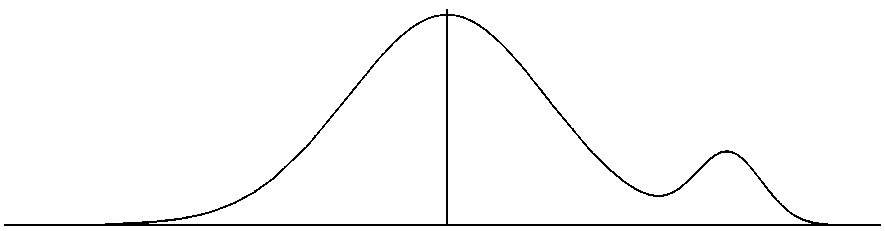

Waterhouse slashes an abscissa and an ordinate onto the board, then

sweeps out a bell shaped curve. On top of the curve, to the right of the

peak, he adds a little hump.

"The tall girls," he explains. "The problem is this notch." He points

to the valley between the main peak and the bump. Then he draws a new peak

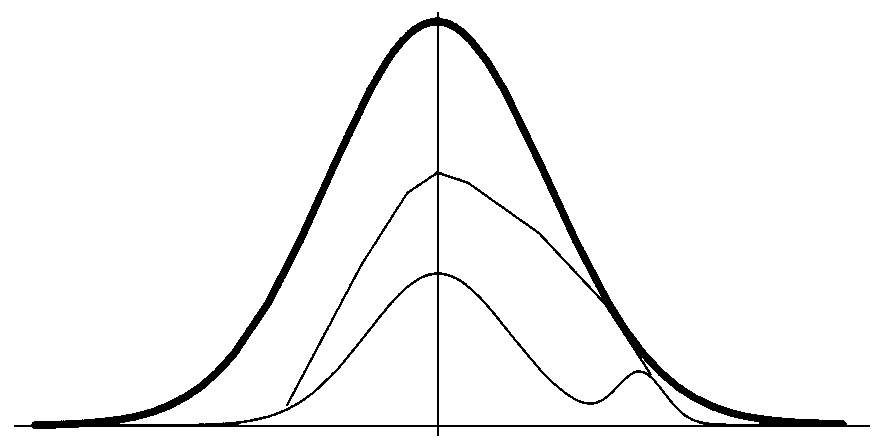

high and wide enough to cover both:

"The tall girls," he explains. "The problem is this notch." He points

to the valley between the main peak and the bump. Then he draws a new peak

high and wide enough to cover both:

"We can do that by planting fake personnel records in Rudy's channel,

giving heights that are taller than the overall average, but shorter than

the bombe girls."

"But now you've dug yourself another hole," Chattan says. He is leaning

back in his officer's swivel chair, holding the cigarette in front of his

face, regarding Waterhouse through a motionless cloud of smoke.

Waterhouse says, "The new curve looks a little better because I filled

in that gap, but it's not really bell shaped. It doesn't tail off right, out

here at the edges. Dr. von Hacklheber will notice that. He'll realize that

someone's been tampering with his channel. To prevent that from happening I

would have to plant more fake records, giving some unusually large and small

values."

"Invent some fake girls who were exceptionally short or tall," Chattan

says.

"We can do that by planting fake personnel records in Rudy's channel,

giving heights that are taller than the overall average, but shorter than

the bombe girls."

"But now you've dug yourself another hole," Chattan says. He is leaning

back in his officer's swivel chair, holding the cigarette in front of his

face, regarding Waterhouse through a motionless cloud of smoke.

Waterhouse says, "The new curve looks a little better because I filled

in that gap, but it's not really bell shaped. It doesn't tail off right, out

here at the edges. Dr. von Hacklheber will notice that. He'll realize that

someone's been tampering with his channel. To prevent that from happening I

would have to plant more fake records, giving some unusually large and small

values."

"Invent some fake girls who were exceptionally short or tall," Chattan

says.

"Yes. That would make the curve tail off in the way that it should.'

Chattan continues to look at him expectantly.

Waterhouse says, "So, the addition of a small number of what would

otherwise be bizarre anomalies makes it all look perfectly normal."

"As I said," Chattan says, "our squad is in North Africa even as we

speak widening the bell curve. Making it all look perfectly normal."

Chapter 15 MEAT

Okay, so Private First Class Gerald Hott, late of Chicago, Illinois,

did not exactly shoot up through the ranks during his fifteen year tenure in

the United States Army. He did, how ever, carve a bitchin' loin roast. He

was as deft with a boning knife as Bobby Shaftoe is with a bayonet. And who

is to say that a military butcher, by conserving the limited resources of a

steer's carcass and by scrupulously observing the mandated sanitary

practices, might not save as many lives as a steely eyed warrior? The

military is not just about killing Nips, Krauts, and Dagoes. It is also

about killing livestock and eating them. Gerald Hott was a front line

warrior who kept his freezer locker as clean as an operating room and so it

is only fitting that he has ended up there.

Bobby Shaftoe makes this little elegy up in his head as he is shivering

in the sub Arctic chill of a formerly French, and now U.S. Army, meat locker

the size and temperature of Greenland, surrounded by the earthly remains of

several herds of cattle and one butcher. He has attended more than a few

military funerals during his brief time in the service, and has always been

bowled over by the skill of the chaplains in coming up with moving elegies

for the departed. He has heard rumors that when the military inducts 4 Fs

who are discovered to have brains, it teaches them to type and assigns them

to sit at desks and type these things out, day after day. Nice duty if you

can get it.

The frozen carcasses dangle from meathooks in long rows. Bobby Shaftoe

gets tenser and tenser as he works his way up and down the aisles, steeling

himself for the bad thing he is about to see. It is almost preferable when

your buddy's head suddenly explodes just as he is puffing his cigarette into

life buildup like this can drive you nuts.

Finally he rounds the end of a row and discovers a man slumbering on

the floor, locked in embrace with a pork carcass, which he was apparently

about to butcher at the time of his death. He has been there for about

twelve hours now and his body temp is hovering around minus ten degrees

Fahrenheit.

Bobby Shaftoe squares himself to face the body and draws a deep breath

of frosty, meat scented air. He clasps his cyanotic hands in front of his

chest in a manner that is both prayerful and good for warming them up. "Dear

Lord," he says out loud. His voice does not echo; the carcasses soak it up.

"Forgive this marine for these, his duties, which he is about to perform,

and while you are at it, by all means forgive this marine's superiors whom

You in Your infinite wisdom have seen fit to bless him with, and forgive

their superiors for getting the whole deal together."

He considers going on at some length but finally decides that this is

no worse than bayonetting Nips and so let's get on with it. He goes to the

locked bodies of PFC Gerald Hott and Frosty the Pig and tries to separate

them without success. He squats by them and gives the former a good look.

Hott is blond. His eyes are half closed, and when Shaftoe shines a

flashlight into the slit, he can see a glint of blue. Hott is a big man,

easily two twenty five in fighting trim, easily two fifty now. Life in a

military kitchen does not make it easy for a fellow to keep his weight down,

or (unfortunately for Hott) his cardiovascular system in any kind of

dependable working order.

Hott and his uniform were both dry when the heart attack happened, so

thank god the fabric is not frozen onto the skin. Shaftoe is able to cut

most of it off with several long strokes of his exquisitely sharpened V 44

"Gung Ho" knife. But the V 44's machetelike nine and a half inch blade is

completely inappropriate for close infighting viz., the denuding of the

armpits and groin and he was told to be careful about inflicting scratches,

so there he has to break out the USMC Marine Raider stiletto, whose slender

double edged seven and a quarter inch blade might have been designed for

exactly this sort of procedure, though the fish shaped handle, which is made

of solid metal, begins freezing to the sweaty palm of Shaftoe's hand after a

while.

Lieutenant Ethridge is hovering outside the locker's tomblike door.

Shaftoe barges past him and heads straight for the building's exit, ignoring

Ethridge's queries: "Shaftoe? How 'bout it?"

He does not stop until he is out of the shade of the building. The

North African sunshine breaks over his body like a washtub of morphine. He

closes his eyes and turns his face into it, holds his frozen hands up to cup

the warmth and let it trickle down his forearms, drip from his elbows.

"How 'bout it?" Ethridge says again.

Shaftoe opens his eyes and looks around.

The harbor's a blue crescent with miles of sere jetties snaking around

each other like diagrams of dance steps. One of them's covered with worn

stumps of ancient bastions and next to it a French battleship lies half

sunk, still piping smoke and steam into the air. All around it, the ships of

Operation Torch are unloading shit faster than you can believe. Cargo nets

rise from the holds of the transports and splat onto the quays like giant

loogies. Longshoremen haul, trucks carry, troops march, French girls smoke

Yankee cigarettes, Algerians propose joint ventures.

Between those ships, and the Army's meat operation, up here on this

rock, is what Bobby Shaftoe takes to be the City of Algiers. To his

discriminating Wisconsinan eye it does not appear to have been built so much

as swept up on the hillside by a tidal wave. A lot of acreage has been

devoted to keeping the fucking sun off, so from above, it has a shuttered up

look about it lots of red tile, decorated with flowers and Arabs. Looks like

a few modern concrete structures (e.g. this meat locker) have been thrown up

by the French in the wake of some kind of vigorous slum clearing offensive.

Still, there's a lot of slums left to be cleared target number one being

this human beehive or anthill just off to Shaftoe's left, the Casbah, they

call it. Maybe it's a neighborhood. Maybe it's a single poorly organized

building. Has to be seen to be believed. Arabs packed into the place like

fraternity pledges into a telephone booth.

Shaftoe turns around and looks again at the meat locker, which is

dangerously exposed to enemy air attack here, but no one gives a fuck

because who cares if the Krauts blow up a bunch of meat?

Lieutenant Ethridge, almost as desperately sunburned as Bobby Shaftoe,

squints.

"Blond," Shaftoe says.

"Okay."

"Blue eyed."

"Good."

"Anteater not mushroom."

"Huh?"

"He's not circumcised, sir!"

"Excellent! How 'bout the other thing?"

"One tattoo, sir!"

Shaftoe is enjoying the slow buildup of tension in Ethridge's voice:

"Describe the tattoo, Sergeant!"

"Sir! It is a commonly seen military design, sir! Consisting of a heart

with a female's name in it."

"What is that name, Sergeant?" Ethridge is on the verge of pissing his

pants.

"Sir! The name inscribed on the tattoo is the following name: Griselda.

Sir!"

"Aaaah!" Lieutenant Ethridge lets loose deep from the diaphragm. Veiled

women turn and look. Over in that Casbah, starved looking, shave needing

ragheads lean out of spindly towers yodeling out of key.

Ethridge shuts up and contents himself with clenching his fists until

they go white. When he speaks again, his voice is hushed with emotion.

"Battles have hinged on lesser strokes of luck than this one, Sergeant!"

"You're telling me!?" Shaftoe says. "When I was on Guadalcanal, sir, we

got trapped in this little cove and pinned down "

"I don't want to hear the lizard story, Sergeant!"

"Sir! Yes, sir!"

***

Once when Bobby Shaftoe was still in Oconomowoc, he had to help his

brother move a mattress up a stairway and learned new respect for the

difficulty of manipulating heavy but floppy objects. Hott, may God have

mercy on his soul, is a heavy S.O.B., and so it is excellent luck that he is

frozen solid. After the Mediterranean sun has its way with him, he is sure

enough going to be floppy. And then some.

All of Shaftoe's men are down in the detachment's staging area. This is

a cave built into a sheer artificial cliff that rises from the

Mediterranean, just above the docks. These caves go on for miles and there

is a boulevard running over the top of them. But even the approaches to

their particular cave have been covered with tents and tarps so that no one,

not even Allied troops, can see what they are up to: namely, looking for any

equipment with 2701 painted on it, painting over the last digit, and

changing it to 2. The first operation is handled by men with green paint and

the second by men with white or black paint.

Shaftoe picks one man from each color group so that the operation as a

whole will not be disrupted. The sun is stunningly powerful here, but in

that cavern, with a cool maritime breeze easing through, it's not really

that bad. The sharp smell of petroleum distillates comes off all of those

warm painted surfaces. To Bobby Shaftoe, it is a comforting smell, because

you never paint stuff when you're in combat. But the smell also makes him a

little tingly, because you frequently paint stuff just before you go into

combat.

Shaftoe is about to brief his three handpicked Marines on what is to

come when the private with black paint on his hands, Daniels, looks past him

and smirks. "What's the lieutenant looking for now do you suppose, Sarge?"

he says.

Shaftoe and Privates Nathan (green paint) and Branph (white) look over

to see that Ethridge has gotten sidetracked. He is going through the

wastebaskets again.

"We have all noticed that Lieutenant Ethridge seems to think it is his

mission in life to go through wastebaskets," Sergeant Shaftoe says in a low,

authoritative voice. "He is an Annapolis graduate."

Ethridge straightens up and, in the most accusatory way possible, holds

up a fistful of pierced and perforated oaktag. "Sergeant! Would you identify

this material?"

"Sir! It is general issue military stencils, Sir!"

"Sergeant! How many letters are there in the alphabet?"

"Twenty six, sir!" responds Shaftoe crisply.

Privates Daniels, Nathan and Branph whistle coolly at each other this

Sergeant Shaftoe is sharp as a tack.

"Now, how many numerals?"

"Ten, sir!"

"And of the thirty six letters and numerals, how many of them are

represented by unused stencils in this wastebasket?"

"Thirty five, sir! All except for the numeral 2, which is the only one

we need to carry out your orders, sir!"

"Have you forgotten the second part of my order, Sergeant?"

"Sir, yes, sir!" No point in lying about it. Officers actually like it

when you forget their orders because it reminds them of how much smarter

they are than you. It makes them feel needed.

"The second part of my order was to take strict measures to leave

behind no trace of the changeover!"

"Sir, yes, I do remember that now, sir!"

Lieutenant Ethridge, who was just a bit huffy first, has now calmed

down quite a bit, which speaks well of him and is duly, silently noted by

all of the men, who have known him for less than six hours. He is now

speaking calmly and conversationally, like a friendly high school teacher.

He is wearing the heavy rimmed black military eyeglasses known in the trade

as RPGs, or Rape Prevention Glasses. They are strapped to his head by a hunk

of black elastic. They make him look like a mental retard. "If some enemy

agent were to go through the contents of this wastebasket, as enemy agents

have been known to do, what would he find?"

"Stencils sir!"

"And if he were to count the numerals and letters, would he notice

anything unusual?"

"Sir! All of them would be clean except for the numeral twos which

would be missing or covered with paint, sir!"

Lieutenant Ethridge says nothing for a few minutes, allowing his

message to sink in. In reality no one knows what the fuck he is talking

about. The atmosphere becomes tinderlike until finally, Sergeant Shaftoe

makes a desperate stab. He turns away from Ethridge and towards the men. "I

want you Marines to get paint on all of those goddamn stencils!" he barks.

The Marines charge the wasteb

"Yes. That would make the curve tail off in the way that it should.'

Chattan continues to look at him expectantly.

Waterhouse says, "So, the addition of a small number of what would

otherwise be bizarre anomalies makes it all look perfectly normal."

"As I said," Chattan says, "our squad is in North Africa even as we

speak widening the bell curve. Making it all look perfectly normal."

Chapter 15 MEAT

Okay, so Private First Class Gerald Hott, late of Chicago, Illinois,

did not exactly shoot up through the ranks during his fifteen year tenure in

the United States Army. He did, how ever, carve a bitchin' loin roast. He

was as deft with a boning knife as Bobby Shaftoe is with a bayonet. And who

is to say that a military butcher, by conserving the limited resources of a

steer's carcass and by scrupulously observing the mandated sanitary

practices, might not save as many lives as a steely eyed warrior? The

military is not just about killing Nips, Krauts, and Dagoes. It is also

about killing livestock and eating them. Gerald Hott was a front line

warrior who kept his freezer locker as clean as an operating room and so it

is only fitting that he has ended up there.

Bobby Shaftoe makes this little elegy up in his head as he is shivering

in the sub Arctic chill of a formerly French, and now U.S. Army, meat locker

the size and temperature of Greenland, surrounded by the earthly remains of

several herds of cattle and one butcher. He has attended more than a few

military funerals during his brief time in the service, and has always been

bowled over by the skill of the chaplains in coming up with moving elegies

for the departed. He has heard rumors that when the military inducts 4 Fs

who are discovered to have brains, it teaches them to type and assigns them

to sit at desks and type these things out, day after day. Nice duty if you

can get it.

The frozen carcasses dangle from meathooks in long rows. Bobby Shaftoe

gets tenser and tenser as he works his way up and down the aisles, steeling

himself for the bad thing he is about to see. It is almost preferable when

your buddy's head suddenly explodes just as he is puffing his cigarette into

life buildup like this can drive you nuts.

Finally he rounds the end of a row and discovers a man slumbering on

the floor, locked in embrace with a pork carcass, which he was apparently

about to butcher at the time of his death. He has been there for about

twelve hours now and his body temp is hovering around minus ten degrees

Fahrenheit.

Bobby Shaftoe squares himself to face the body and draws a deep breath

of frosty, meat scented air. He clasps his cyanotic hands in front of his

chest in a manner that is both prayerful and good for warming them up. "Dear

Lord," he says out loud. His voice does not echo; the carcasses soak it up.

"Forgive this marine for these, his duties, which he is about to perform,

and while you are at it, by all means forgive this marine's superiors whom

You in Your infinite wisdom have seen fit to bless him with, and forgive

their superiors for getting the whole deal together."

He considers going on at some length but finally decides that this is

no worse than bayonetting Nips and so let's get on with it. He goes to the

locked bodies of PFC Gerald Hott and Frosty the Pig and tries to separate

them without success. He squats by them and gives the former a good look.

Hott is blond. His eyes are half closed, and when Shaftoe shines a

flashlight into the slit, he can see a glint of blue. Hott is a big man,

easily two twenty five in fighting trim, easily two fifty now. Life in a

military kitchen does not make it easy for a fellow to keep his weight down,

or (unfortunately for Hott) his cardiovascular system in any kind of

dependable working order.

Hott and his uniform were both dry when the heart attack happened, so

thank god the fabric is not frozen onto the skin. Shaftoe is able to cut

most of it off with several long strokes of his exquisitely sharpened V 44

"Gung Ho" knife. But the V 44's machetelike nine and a half inch blade is

completely inappropriate for close infighting viz., the denuding of the

armpits and groin and he was told to be careful about inflicting scratches,

so there he has to break out the USMC Marine Raider stiletto, whose slender

double edged seven and a quarter inch blade might have been designed for

exactly this sort of procedure, though the fish shaped handle, which is made

of solid metal, begins freezing to the sweaty palm of Shaftoe's hand after a

while.

Lieutenant Ethridge is hovering outside the locker's tomblike door.

Shaftoe barges past him and heads straight for the building's exit, ignoring

Ethridge's queries: "Shaftoe? How 'bout it?"

He does not stop until he is out of the shade of the building. The

North African sunshine breaks over his body like a washtub of morphine. He

closes his eyes and turns his face into it, holds his frozen hands up to cup

the warmth and let it trickle down his forearms, drip from his elbows.

"How 'bout it?" Ethridge says again.

Shaftoe opens his eyes and looks around.

The harbor's a blue crescent with miles of sere jetties snaking around

each other like diagrams of dance steps. One of them's covered with worn

stumps of ancient bastions and next to it a French battleship lies half

sunk, still piping smoke and steam into the air. All around it, the ships of

Operation Torch are unloading shit faster than you can believe. Cargo nets

rise from the holds of the transports and splat onto the quays like giant

loogies. Longshoremen haul, trucks carry, troops march, French girls smoke

Yankee cigarettes, Algerians propose joint ventures.

Between those ships, and the Army's meat operation, up here on this

rock, is what Bobby Shaftoe takes to be the City of Algiers. To his

discriminating Wisconsinan eye it does not appear to have been built so much

as swept up on the hillside by a tidal wave. A lot of acreage has been

devoted to keeping the fucking sun off, so from above, it has a shuttered up

look about it lots of red tile, decorated with flowers and Arabs. Looks like

a few modern concrete structures (e.g. this meat locker) have been thrown up

by the French in the wake of some kind of vigorous slum clearing offensive.

Still, there's a lot of slums left to be cleared target number one being

this human beehive or anthill just off to Shaftoe's left, the Casbah, they

call it. Maybe it's a neighborhood. Maybe it's a single poorly organized

building. Has to be seen to be believed. Arabs packed into the place like

fraternity pledges into a telephone booth.

Shaftoe turns around and looks again at the meat locker, which is

dangerously exposed to enemy air attack here, but no one gives a fuck

because who cares if the Krauts blow up a bunch of meat?

Lieutenant Ethridge, almost as desperately sunburned as Bobby Shaftoe,

squints.

"Blond," Shaftoe says.

"Okay."

"Blue eyed."

"Good."

"Anteater not mushroom."

"Huh?"

"He's not circumcised, sir!"

"Excellent! How 'bout the other thing?"

"One tattoo, sir!"

Shaftoe is enjoying the slow buildup of tension in Ethridge's voice:

"Describe the tattoo, Sergeant!"

"Sir! It is a commonly seen military design, sir! Consisting of a heart

with a female's name in it."

"What is that name, Sergeant?" Ethridge is on the verge of pissing his

pants.

"Sir! The name inscribed on the tattoo is the following name: Griselda.

Sir!"

"Aaaah!" Lieutenant Ethridge lets loose deep from the diaphragm. Veiled

women turn and look. Over in that Casbah, starved looking, shave needing

ragheads lean out of spindly towers yodeling out of key.

Ethridge shuts up and contents himself with clenching his fists until

they go white. When he speaks again, his voice is hushed with emotion.

"Battles have hinged on lesser strokes of luck than this one, Sergeant!"

"You're telling me!?" Shaftoe says. "When I was on Guadalcanal, sir, we

got trapped in this little cove and pinned down "

"I don't want to hear the lizard story, Sergeant!"

"Sir! Yes, sir!"

***

Once when Bobby Shaftoe was still in Oconomowoc, he had to help his

brother move a mattress up a stairway and learned new respect for the

difficulty of manipulating heavy but floppy objects. Hott, may God have

mercy on his soul, is a heavy S.O.B., and so it is excellent luck that he is

frozen solid. After the Mediterranean sun has its way with him, he is sure

enough going to be floppy. And then some.

All of Shaftoe's men are down in the detachment's staging area. This is

a cave built into a sheer artificial cliff that rises from the

Mediterranean, just above the docks. These caves go on for miles and there

is a boulevard running over the top of them. But even the approaches to

their particular cave have been covered with tents and tarps so that no one,

not even Allied troops, can see what they are up to: namely, looking for any

equipment with 2701 painted on it, painting over the last digit, and

changing it to 2. The first operation is handled by men with green paint and

the second by men with white or black paint.

Shaftoe picks one man from each color group so that the operation as a

whole will not be disrupted. The sun is stunningly powerful here, but in

that cavern, with a cool maritime breeze easing through, it's not really

that bad. The sharp smell of petroleum distillates comes off all of those

warm painted surfaces. To Bobby Shaftoe, it is a comforting smell, because

you never paint stuff when you're in combat. But the smell also makes him a

little tingly, because you frequently paint stuff just before you go into

combat.

Shaftoe is about to brief his three handpicked Marines on what is to

come when the private with black paint on his hands, Daniels, looks past him

and smirks. "What's the lieutenant looking for now do you suppose, Sarge?"

he says.

Shaftoe and Privates Nathan (green paint) and Branph (white) look over

to see that Ethridge has gotten sidetracked. He is going through the

wastebaskets again.

"We have all noticed that Lieutenant Ethridge seems to think it is his

mission in life to go through wastebaskets," Sergeant Shaftoe says in a low,

authoritative voice. "He is an Annapolis graduate."

Ethridge straightens up and, in the most accusatory way possible, holds

up a fistful of pierced and perforated oaktag. "Sergeant! Would you identify

this material?"

"Sir! It is general issue military stencils, Sir!"

"Sergeant! How many letters are there in the alphabet?"

"Twenty six, sir!" responds Shaftoe crisply.

Privates Daniels, Nathan and Branph whistle coolly at each other this

Sergeant Shaftoe is sharp as a tack.

"Now, how many numerals?"

"Ten, sir!"

"And of the thirty six letters and numerals, how many of them are

represented by unused stencils in this wastebasket?"

"Thirty five, sir! All except for the numeral 2, which is the only one

we need to carry out your orders, sir!"

"Have you forgotten the second part of my order, Sergeant?"

"Sir, yes, sir!" No point in lying about it. Officers actually like it

when you forget their orders because it reminds them of how much smarter

they are than you. It makes them feel needed.

"The second part of my order was to take strict measures to leave

behind no trace of the changeover!"

"Sir, yes, I do remember that now, sir!"

Lieutenant Ethridge, who was just a bit huffy first, has now calmed

down quite a bit, which speaks well of him and is duly, silently noted by

all of the men, who have known him for less than six hours. He is now

speaking calmly and conversationally, like a friendly high school teacher.

He is wearing the heavy rimmed black military eyeglasses known in the trade

as RPGs, or Rape Prevention Glasses. They are strapped to his head by a hunk

of black elastic. They make him look like a mental retard. "If some enemy

agent were to go through the contents of this wastebasket, as enemy agents

have been known to do, what would he find?"

"Stencils sir!"

"And if he were to count the numerals and letters, would he notice

anything unusual?"

"Sir! All of them would be clean except for the numeral twos which

would be missing or covered with paint, sir!"

Lieutenant Ethridge says nothing for a few minutes, allowing his

message to sink in. In reality no one knows what the fuck he is talking

about. The atmosphere becomes tinderlike until finally, Sergeant Shaftoe

makes a desperate stab. He turns away from Ethridge and towards the men. "I

want you Marines to get paint on all of those goddamn stencils!" he barks.

The Marines charge the wasteb