�Нил Стивенсон. Криптономикон (engl)�

�Neal Stephenson. Cryptonomicon�

Neal Stephenson,

CRYPTONOMICON

Neal Stephenson,

CRYPTONOMICON

"There is a remarkably close parallel between the problems of the physicist

and those of the cryptographer. The system on which a message is enciphered

corresponds to the laws of the universe, the intercepted messages to the

evidence available, the keys for a day or a message to important constants

which have to be determined. The correspondence is very close, but the

subject matter of cryptography is very easily dealt with by discrete

machinery, physics not so easily."

Alan Turing

This morning [Imelda Marcos] offered the latest in a series of explanations

of the billions of dollars that she and her husband, who died in 1989, are

believed to have stolen during his presidency.

"It so coincided that Marcos had money," she said. "After the Bretton Woods

agreement he started buying gold from Fort Knox. Three thousand tons, then

4,000 tons. I have documents for these: 7,000 tons. Marcos was so smart. He

had it all. It's funny; America didn't understand him."

The New York Times, Monday, 4 March, 1996

Prologue

Two tires fly. Two wail.

A bamboo grove, all chopped down

From it, warring songs.

...is the best that Corporal Bobby Shaftoe can do on short notice he's

standing on the running board, gripping his Springfield with one hand and

the rearview mirror with the other, so counting the syllables on his fingers

is out of the question. Is "tires" one syllable or two? How about "wail?"

The truck finally makes up its mind not to tip over, and thuds back onto

four wheels. The wail and the moment are lost. Bobby can still hear the

coolies singing, though, and now too there's the gunlike snicking of the

truck's clutch linkage as Private Wiley downshifts. Could Wiley be losing

his nerve? And, in the back, under the tarps, a ton and a half of file

cabinets clanking, code books slaloming, fuel spanking the tanks of Station

Alpha's electrical generator. The modern world's hell on haiku writers:

"Electrical generator" is, what, eight syllables? You couldn't even fit that

onto the second line!

"Are we allowed to run over people?" Private Wiley inquires, and then

mashes the horn button before Bobby Shaftoe can answer. A Sikh policeman

hurdles a night soil cart. Shaftoe's gut reaction is: Sure, what're they

going to do, declare war on us? but as the highest ranking man on this truck

he's probably supposed to be using his head or something, so he doesn't

blurt it out just yet. He takes stock of the situation:

Shanghai, 1645 hours, Friday, the 28th of November 1941. Bobby Shaftoe,

and the other half dozen Marines on his truck, are staring down the length

of Kiukiang Road, onto which they've just made this careening high speed

turn. Cathedral's going by to the right, so that means they are, what? two

blocks away from the Bund. A Yangtze River Patrol gunboat is tied up there,

waiting for the stuff they've got in the back of this truck. The only real

problem is that those particular two blocks are inhabited by about five

million Chinese people.

Now these Chinese are sophisticated urbanites, not suntanned yokels

who've never seen cars before they'll get out of your way if you drive fast

and honk your horn. And indeed many of them flee to one side of the street

or the other, producing the illusion that the truck is moving faster than

the forty three miles an hour shown on its speedometer.

But the bamboo grove in Bobby Shaftoe's haiku has not been added just

to put a little Oriental flavor into the poem and wow the folks back home in

Oconomowoc. There is a lot of heavy bamboo in front of this truck, dozens of

makeshift turnpikes blocking their path to the river, for the officers of

the U.S. Navy's Asiatic Fleet, and of the Fourth Marines, who dreamed up

this little operation forgot to take the Friday Afternoon factor into

account. As Bobby Shaftoe could've explained to them, if only they'd

bothered to ask a poor dumb jarhead, their route took them through the heart

of the banking district. Here you've got the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank of

course, City Bank, Chase Manhattan, the Bank of America, and BBME and the

Agricultural Bank of China and any number of crappy little provincial banks,

and several of those banks have contracts with what's left of the Chinese

Government to print currency. It must be a cutthroat business because they

slash costs by printing it on old newspapers, and if you know how to read

Chinese, you can see last year's news stories and polo scores peeking

through the colored numbers and pictures that transform these pieces of

paper into legal tender.

As every chicken peddler and rickshaw operator in Shanghai knows, the

money printing contracts stipulate that all of the bills these banks print

have to be backed by such and such an amount of silver; i.e., anyone should

be able to walk into one of those banks at the end of Kiukiang Road and slap

down a pile of bills and (provided that those bills were printed by that

same bank) receive actual metallic silver in exchange.

Now if China weren't right in the middle of getting systematically

drawn and quartered by the Empire of Nippon, it would probably send official

bean counters around to keep tabs on how much silver was actually present in

these banks' vaults, and it would all be quiet and orderly. But as it

stands, the only thing keeping these banks honest is the other banks.

Here's how they do it: during the normal course of business, lots of

paper money will pass over the counters of (say) Chase Manhattan Bank.

They'll take it into a back room and sort it, throwing into money boxes (a

couple of feet square and a yard deep, with ropes on the four corners) all

of the bills that were printed by (say) Bank of America in one, all of the

City Bank bills into another. Then, on Friday afternoon they will bring in

coolies. Each coolie, or pair of coolies, will of course have his great big

long bamboo pole with him a coolie without his pole is like a China Marine

without his nickel plated bayonet and will poke their pole through the ropes

on the corners of the box. Then one coolie will get underneath each end of

the pole, hoisting the box into the air. They have to move in unison or else

the box begins flailing around and everything gets out of whack. So as they

head towards their destination whatever bank whose name is printed on the

bills in their box they sing to each other, and plant their feet on the

pavement in time to the music. The pole's pretty long, so they are that far

apart, and they have to sing loud to hear each other, and of course each

pair of coolies in the street is singing their own particular song, trying

to drown out all of the others so that they don't get out of step.

So ten minutes before closing time on Friday afternoon, the doors of

many banks burst open and numerous pairs of coolies march in singing, like

the curtain raiser on a fucking Broadway musical, slam their huge boxes of

tattered currency down, and demand silver in exchange. All of the banks do

this to each other. Sometimes, they'll all do it on the same Friday,

particularly at times like 28 November 1941, when even a grunt like Bobby

Shaftoe can understand that it's better to be holding silver than piles of

old cut up newspaper. And that is why, once the normal pedestrians and food

cart operators and furious Sikh cops have scurried out of the way, and

plastered themselves up against the clubs and shops and bordellos on

Kiukiang Road, Bobby Shaftoe and the other Marines on the truck still cannot

even see the gunboat that is their destination, because of this horizontal

forest of mighty bamboo poles. They cannot even hear the honking of their

own truck horn because of the wild throbbing pentatonic cacophony of coolies

singing. This ain't just your regular Friday P.M. Shanghai bank district

money rush. This is an ultimate settling of accounts before the whole

Eastern Hemisphere catches fire. The millions of promises printed on those

slips of bumwad will all be kept or broken in the next ten minutes; actual

pieces of silver and gold will move, or they won't. It is some kind of

fiduciary Judgment Day.

"Jesus Christ, I can't " Private Wiley hollers.

"The captain said don't stop for any reason whatsofuckinever," Shaftoe

reminds him. He's not telling Wiley to run over the coolies, he's reminding

Wiley that if he refrains from running over them, they will have some

explaining to do which will be complicated by the fact that the captain's

right behind them in a car stuffed with Tommy Gun toting China Marines. And

from the way the captain's been acting about this Station Alpha thing, it's

pretty clear that he already has a few preliminary strap marks on his ass,

courtesy of some admiral in Pearl Harbor or even (drumroll) Marine Barracks,

Eight and Eye Streets Southeast, Washington, D.C.

***

Shaftoe and the other Marines have always known Station Alpha as a

mysterious claque of pencil necked swabbies who hung out on the roof of a

building in the International Settlement in a shack of knot pocked cargo

pallet planks with antennas sticking out of it every which way. If you stood

there long enough you could see some of those antennas moving, zeroing in on

something out to sea. Shaftoe even wrote a haiku about it:

Antenna searches

Retriever's nose in the wind

Ether's far secrets

This was only his second haiku ever clearly not up to November 1941

standards and he cringes to remember it.

But in no way did any of the Marines comprehend what a big deal Station

Alpha was until today. Their job had turned out to involve wrapping a ton of

equipment and several tons of paper in tarps and moving it out of doors.

Then they spent Thursday tearing the shack apart, making it into a bonfire,

and burning certain books and papers.

"Sheeeyit!" Private Wiley hollers. Only a few of the coolies have

gotten out of the way, or even seen them. But then there is this fantastic

boom from the river, like the sound of a mile thick bamboo pole being

snapped over God's knee. Half a second later there're no coolies in the

street anymore just a lot of boxes with unmanned bamboo poles teeter

tottering on them, bonging into the streets like wind chimes. Above, a furry

mushroom of grey smoke rises from the gunboat. Wiley shifts up to high gear

and floors it. Shaftoe cringes against the truck's door and lowers his head,

hoping that his campy Great War doughboy helmet will be good for something.

Then money boxes start to rupture and explode as the truck rams through

them. Shaftoe peers up through a blizzard of notes and sees giant bamboo

poles soaring and bounding and windmilling toward the waterfront.

The leaves of Shanghai:

Pale doorways in a steel sky.

Winter has begun.

Chapter 1 BARRENS

Let's set the existence of God issue aside for a later volume, and just

stipulate that in some way, self replicating organisms came into existence

on this planet and immediately began trying to get rid of each other, either

by spamming their environments with rough copies of themselves, or by more

direct means which hardly need to be belabored. Most of them failed, and

their genetic legacy was erased from the universe forever, but a few found

some way to survive and to propagate. After about three billion years of

this sometimes zany, frequently tedious fugue of carnality and carnage,

Godfrey Waterhouse IV was born, in Murdo, South Dakota, to Blanche, the wife

of a Congregational preacher named Bunyan Waterhouse. Like every other

creature on the face of the earth, Godfrey was, by birthright, a stupendous

badass, albeit in the somewhat narrow technical sense that he could trace

his ancestry back up a long line of slightly less highly evolved stupendous

badasses to that first self replicating gizmo which, given the number and

variety of its descendants, might justifiably be described as the most

stupendous badass of all time. Everyone and everything that wasn't a

stupendous badass was dead.

As nightmarishly lethal, memetically programmed death machines went,

these were the nicest you could ever hope to meet. In the tradition of his

namesake (the Puritan writer John Bunyan, who spent much of his life in

jail, or trying to avoid it) the Rev. Waterhouse did not preach in any one

place for long. The church moved him from one small town in the Dakotas to

another every year or two. It is possible that Godfrey found the lifestyle

more than a little alienating, for, sometime during the course of his

studies at Fargo Congregational College, he bolted from the fold and, to the

enduring agony of his parents, fell into worldly pursuits, and ended up,

somehow, getting a Ph.D. in Classics from a small private university in

Ohio. Academics being no less nomadic than Congregational preachers, he took

work where he could find it. He became a Professor of Greek and Latin at

Bolger Christian College (enrollment 322) in West Point, Virginia, where the

Mattaponi and Pamunkey Rivers came together to form the estuarial James, and

the loathsome fumes of the big paper mill permeated every drawer, every

closet, even the interior pages of books. Godfrey's young bride, nee Alice

Pritchard, who had grown up following her itinerant preacher father across

the vastnesses of eastern Montana where air smelt of snow and sage threw up

for three months. Six months later she gave birth to Lawrence Pritchard

Waterhouse.

The boy had a peculiar relationship with sound. When a fire engine

passed, he was not troubled by the siren's howl or the bell's clang. But

when a hornet got into the house and swung across the ceiling in a broad

Lissajous, droning almost inaudibly, he cried in pain at the noise. And if

he saw or smelled something that scared him, he would clap his hands over

his ears.

One noise that troubled him not at all was the pipe organ in the chapel

at Bolger Christian College. The chapel itself was nothing worth mentioning,

but the organ had been endowed by the paper mill family and would have

sufficed for a church four times the size. It nicely complemented the

organist, a retired high school math teacher who felt that certain

attributes of the Lord (violence and capriciousness in the Old Testament,

majesty and triumph in the New) could be directly conveyed into the souls of

the enpewed sinners through a kind of frontal sonic impregnation. That he

ran the risk of blowing out the stained glass windows was of no consequence

since no one liked them anyway, and the paper mill fumes were gnawing at the

interstitial lead. But after one little old lady too many staggered down the

aisle after a service, reeling from tinnitus, and made a barbed comment to

the minister about the exceedingly dramatic music, the organist was

replaced.

Nevertheless, he continued to give lessons on the instrument. Students

were not allowed to touch the organ until they were proficient at the piano,

and when this was explained to Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse, he taught

himself in three weeks, how to play a Bach fugue, and signed up for organ

lessons. Since he was only five years old at the time, he was unable to

reach both the manuals and the pedals, and had to play standing or rather

strolling, from pedal to pedal.

When Lawrence was twelve, the organ broke down. That paper mill family

had not left any endowment for maintenance, so the math teacher decided to

have a crack at it. He was in poor health and required a nimble assistant:

Lawrence, who helped him open up the hood of the thing. For the first time

in all those years, the boy saw what had been happening when he had been

pressing those keys.

For each stop each timbre, or type of sound, that the organ could make

(viz. blockflöte, trumpet, piccolo) there was a separate row of pipes,

arranged in a line from long to short. Long pipes made low notes, short

high. The tops of the pipes defined a graph: not a straight line but an

upward tending curve. The organist/math teacher sat down with a few loose

pipes, a pencil, and paper, and helped Lawrence figure out why. When

Lawrence understood, it was as if the math teacher had suddenly played the

good part of Bach's Fantasia and Fugue in G Minor on a pipe organ the size

of the Spiral Nebula in Andromeda the part where Uncle Johann dissects the

architecture of the Universe in one merciless descending ever mutating

chord, as if his foot is thrusting through skidding layers of garbage until

it finally strikes bedrock. In particular, the final steps of the organist's

explanation were like a falcon's dive through layer after layer of pretense

and illusion, thrilling or sickening or confusing depending on what you

were. The heavens were riven open. Lawrence glimpsed choirs of angels

ranking off into geometrical infinity.

The pipes sprouted in parallel ranks from a broad flat box of

compressed air. All of the pipes for a given note but belonging to different

stops lined up with each other along one axis. All of the pipes for a given

stop but tuned at different pitches lined up with each other along the

other, perpendicular axis. Down there in the flat box of air, then, was a

mechanism that got air to the right pipes at the right times. When a key or

pedal was depressed, all of the pipes capable of sounding the corresponding

note would speak, as long as their stops were pulled out.

Mechanically, all of this was handled in a fashion that was perfectly

clear, simple, and logical. Lawrence had supposed that the machine must be

at least as complicated as the most intricate fugue that could be played on

it. Now he had learned that a machine, simple in its design, could produce

results of infinite complexity.

Stops were rarely used alone. They tended to be piled on top of each

other in combinations that were designed to take advantage of the available

harmonics (more tasty mathematics here!). Certain combinations in particular

were used over and over again. Lots of blockflötes, in varying lengths, for

the quiet Offertory, for example. The organ included an ingenious mechanism

called the preset, which enabled the organist to select a particular

combination of stops stops he himself had chosen instantly. He would punch a

button and several stops would bolt out from the console, driven by

pneumatic pressure, and in that instant the organ would become a different

instrument with entirely new timbres.

The next summer both Lawrence and Alice, his mother, were colonized by

a distant cousin a stupendous badass of a virus. Lawrence escaped from it

with an almost imperceptible tendency to drag one of his feet. Alice wound

up in an iron lung. Later, unable to cough effectively, she got pneumonia

and died.

Lawrence's father, Godfrey, freely confessed that he was not equal to

the burdens now laid on his shoulders. He resigned from his position at the

small college in Virginia and moved, with his son, to a small house in

Moorhead, Minnesota, next door to where Bunyan and Blanche had settled.

Later he got a job teaching at a nearby normal school.

At this point, all of the responsible adults in Lawrence's life seemed

to arrive at a tacit agreement that the best way to raise him certainly the

easiest was to leave him alone. On the rare occasions when Lawrence

requested adult intervention in his life, he was usually asking questions

that no one could answer. At the age of sixteen, having found nothing in the

local school system to challenge him, Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse went off

to college. He matriculated at Iowa State College, which among other things

was the site of a Naval ROTC installation in which he was forcibly enrolled.

The Iowa State Naval ROTC had a band, and was delighted to hear that

Lawrence had an interest in music. Since it was hard to drill on the deck of

a dreadnought while playing a pipe organ, they issued him a glockenspiel and

a couple of little dingers.

When not marching back and forth on the flood plain of the Skunk River

making loud dinging noises, Lawrence was majoring in mechanical engineering.

He ended up doing poorly in this area because he had fallen in with a

Bulgarian professor named John Vincent Atanasoff and his graduate student,

Clifford Berry, who were building a machine that was intended to automate

the solution of some especially tedious differential equations.

The basic problem for Lawrence was that he was lazy. He had figured out

that everything was much simpler if, like Superman with his X ray vision,

you just stared through the cosmetic distractions and saw the underlying

mathematical skeleton. Once you found the math in a thing, you knew

everything about it, and you could manipulate it to your heart's content

with nothing more than a pencil and a napkin. He saw it in the curve of the

silver bars on his glockenspiel, saw it in the catenary arch of a bridge and

in the capacitor studded drum of Atanasoff and Berry's computing machine.

Actually pounding on the glockenspiel, riveting the bridge together, or

trying to figure out why the computing machine wasn't working were not as

interesting to him.

Consequently he got poor grades. From time to time, though, he would

perform some stunt on the blackboard that would leave his professor weak in

the knees and the other students baffled and hostile. Word got around.

At the same time, his grandmother Blanche was invoking her extensive

Congregational connections, working the angles on Lawrence's behalf, totally

unbeknownst to him. Her efforts culminated in triumph when Lawrence was

awarded an obscure scholarship, endowed by a St. Paul oat processing heir,

whose purpose was to send Midwestern Congregationalists to the Ivy League

for one year, which (evidently) was deemed a long enough period of time to

raise their IQs by a few crucial points but not long enough to debauch them.

So Lawrence got to be a sophomore in Princeton.

Now Princeton was an august school and going there was a great honor,

but no one got around to mentioning either of these facts to Lawrence, who

had no way of knowing. This had bad and good consequences. He accepted the

scholarship with a faintness of gratitude that infuriated the oat lord. On

the other hand, he adjusted to Princeton easily because it was just another

place . It reminded him of the nicer bits of Virginia, and there were some

nice pipe organs in town, though he was not all that happy with his

engineering homework of bridge designing and sprocket cutting problems. As

always, these eventually came down to math, most of which he could handle

easily. From time to time he would get stuck, though, which led him to the

Fine Hall: the headquarters of the Math Department.

There was a motley assortment of fellows wandering around in Fine Hall,

many sporting British or European accents. Administratively speaking, many

of these fellows were not members of the Math Department at all, but a

separate thing called IAS, which stood for Institute for Advanced something

or other. But they were all in the same building and they all knew a thing

or two about math, so the distinction didn't exist for Lawrence.

Quite a few of these men would pretend shyness when Lawrence sought

their advice, but others were at least willing to hear him out. For example:

he had come up with a way to solve a difficult sprocket tooth shape problem

that, as normally solved by engineers, would require any number of perfectly

reasonable but aesthetically displeasing approximations. Lawrence's solution

would provide exact results. The only draw back was that it would require a

quintillion slide rule operators a quintillion years to solve. Lawrence was

working on a radically different approach that, if it worked, would bring

those figures down to a trillion and a trillion respectively. Unfortunately,

Lawrence was unable to interest anyone at Fine Hall in anything as prosaic

as gears, until all of a sudden he made friends with an energetic British

fellow, whose name he promptly forgot, but who had been doing a lot of

literal sprocket making himself lately. This fellow was trying to build, of

all things, a mechanical calculating machine specifically a machine to

calculate certain values of the Riemann Zeta Function

"There is a remarkably close parallel between the problems of the physicist

and those of the cryptographer. The system on which a message is enciphered

corresponds to the laws of the universe, the intercepted messages to the

evidence available, the keys for a day or a message to important constants

which have to be determined. The correspondence is very close, but the

subject matter of cryptography is very easily dealt with by discrete

machinery, physics not so easily."

Alan Turing

This morning [Imelda Marcos] offered the latest in a series of explanations

of the billions of dollars that she and her husband, who died in 1989, are

believed to have stolen during his presidency.

"It so coincided that Marcos had money," she said. "After the Bretton Woods

agreement he started buying gold from Fort Knox. Three thousand tons, then

4,000 tons. I have documents for these: 7,000 tons. Marcos was so smart. He

had it all. It's funny; America didn't understand him."

The New York Times, Monday, 4 March, 1996

Prologue

Two tires fly. Two wail.

A bamboo grove, all chopped down

From it, warring songs.

...is the best that Corporal Bobby Shaftoe can do on short notice he's

standing on the running board, gripping his Springfield with one hand and

the rearview mirror with the other, so counting the syllables on his fingers

is out of the question. Is "tires" one syllable or two? How about "wail?"

The truck finally makes up its mind not to tip over, and thuds back onto

four wheels. The wail and the moment are lost. Bobby can still hear the

coolies singing, though, and now too there's the gunlike snicking of the

truck's clutch linkage as Private Wiley downshifts. Could Wiley be losing

his nerve? And, in the back, under the tarps, a ton and a half of file

cabinets clanking, code books slaloming, fuel spanking the tanks of Station

Alpha's electrical generator. The modern world's hell on haiku writers:

"Electrical generator" is, what, eight syllables? You couldn't even fit that

onto the second line!

"Are we allowed to run over people?" Private Wiley inquires, and then

mashes the horn button before Bobby Shaftoe can answer. A Sikh policeman

hurdles a night soil cart. Shaftoe's gut reaction is: Sure, what're they

going to do, declare war on us? but as the highest ranking man on this truck

he's probably supposed to be using his head or something, so he doesn't

blurt it out just yet. He takes stock of the situation:

Shanghai, 1645 hours, Friday, the 28th of November 1941. Bobby Shaftoe,

and the other half dozen Marines on his truck, are staring down the length

of Kiukiang Road, onto which they've just made this careening high speed

turn. Cathedral's going by to the right, so that means they are, what? two

blocks away from the Bund. A Yangtze River Patrol gunboat is tied up there,

waiting for the stuff they've got in the back of this truck. The only real

problem is that those particular two blocks are inhabited by about five

million Chinese people.

Now these Chinese are sophisticated urbanites, not suntanned yokels

who've never seen cars before they'll get out of your way if you drive fast

and honk your horn. And indeed many of them flee to one side of the street

or the other, producing the illusion that the truck is moving faster than

the forty three miles an hour shown on its speedometer.

But the bamboo grove in Bobby Shaftoe's haiku has not been added just

to put a little Oriental flavor into the poem and wow the folks back home in

Oconomowoc. There is a lot of heavy bamboo in front of this truck, dozens of

makeshift turnpikes blocking their path to the river, for the officers of

the U.S. Navy's Asiatic Fleet, and of the Fourth Marines, who dreamed up

this little operation forgot to take the Friday Afternoon factor into

account. As Bobby Shaftoe could've explained to them, if only they'd

bothered to ask a poor dumb jarhead, their route took them through the heart

of the banking district. Here you've got the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank of

course, City Bank, Chase Manhattan, the Bank of America, and BBME and the

Agricultural Bank of China and any number of crappy little provincial banks,

and several of those banks have contracts with what's left of the Chinese

Government to print currency. It must be a cutthroat business because they

slash costs by printing it on old newspapers, and if you know how to read

Chinese, you can see last year's news stories and polo scores peeking

through the colored numbers and pictures that transform these pieces of

paper into legal tender.

As every chicken peddler and rickshaw operator in Shanghai knows, the

money printing contracts stipulate that all of the bills these banks print

have to be backed by such and such an amount of silver; i.e., anyone should

be able to walk into one of those banks at the end of Kiukiang Road and slap

down a pile of bills and (provided that those bills were printed by that

same bank) receive actual metallic silver in exchange.

Now if China weren't right in the middle of getting systematically

drawn and quartered by the Empire of Nippon, it would probably send official

bean counters around to keep tabs on how much silver was actually present in

these banks' vaults, and it would all be quiet and orderly. But as it

stands, the only thing keeping these banks honest is the other banks.

Here's how they do it: during the normal course of business, lots of

paper money will pass over the counters of (say) Chase Manhattan Bank.

They'll take it into a back room and sort it, throwing into money boxes (a

couple of feet square and a yard deep, with ropes on the four corners) all

of the bills that were printed by (say) Bank of America in one, all of the

City Bank bills into another. Then, on Friday afternoon they will bring in

coolies. Each coolie, or pair of coolies, will of course have his great big

long bamboo pole with him a coolie without his pole is like a China Marine

without his nickel plated bayonet and will poke their pole through the ropes

on the corners of the box. Then one coolie will get underneath each end of

the pole, hoisting the box into the air. They have to move in unison or else

the box begins flailing around and everything gets out of whack. So as they

head towards their destination whatever bank whose name is printed on the

bills in their box they sing to each other, and plant their feet on the

pavement in time to the music. The pole's pretty long, so they are that far

apart, and they have to sing loud to hear each other, and of course each

pair of coolies in the street is singing their own particular song, trying

to drown out all of the others so that they don't get out of step.

So ten minutes before closing time on Friday afternoon, the doors of

many banks burst open and numerous pairs of coolies march in singing, like

the curtain raiser on a fucking Broadway musical, slam their huge boxes of

tattered currency down, and demand silver in exchange. All of the banks do

this to each other. Sometimes, they'll all do it on the same Friday,

particularly at times like 28 November 1941, when even a grunt like Bobby

Shaftoe can understand that it's better to be holding silver than piles of

old cut up newspaper. And that is why, once the normal pedestrians and food

cart operators and furious Sikh cops have scurried out of the way, and

plastered themselves up against the clubs and shops and bordellos on

Kiukiang Road, Bobby Shaftoe and the other Marines on the truck still cannot

even see the gunboat that is their destination, because of this horizontal

forest of mighty bamboo poles. They cannot even hear the honking of their

own truck horn because of the wild throbbing pentatonic cacophony of coolies

singing. This ain't just your regular Friday P.M. Shanghai bank district

money rush. This is an ultimate settling of accounts before the whole

Eastern Hemisphere catches fire. The millions of promises printed on those

slips of bumwad will all be kept or broken in the next ten minutes; actual

pieces of silver and gold will move, or they won't. It is some kind of

fiduciary Judgment Day.

"Jesus Christ, I can't " Private Wiley hollers.

"The captain said don't stop for any reason whatsofuckinever," Shaftoe

reminds him. He's not telling Wiley to run over the coolies, he's reminding

Wiley that if he refrains from running over them, they will have some

explaining to do which will be complicated by the fact that the captain's

right behind them in a car stuffed with Tommy Gun toting China Marines. And

from the way the captain's been acting about this Station Alpha thing, it's

pretty clear that he already has a few preliminary strap marks on his ass,

courtesy of some admiral in Pearl Harbor or even (drumroll) Marine Barracks,

Eight and Eye Streets Southeast, Washington, D.C.

***

Shaftoe and the other Marines have always known Station Alpha as a

mysterious claque of pencil necked swabbies who hung out on the roof of a

building in the International Settlement in a shack of knot pocked cargo

pallet planks with antennas sticking out of it every which way. If you stood

there long enough you could see some of those antennas moving, zeroing in on

something out to sea. Shaftoe even wrote a haiku about it:

Antenna searches

Retriever's nose in the wind

Ether's far secrets

This was only his second haiku ever clearly not up to November 1941

standards and he cringes to remember it.

But in no way did any of the Marines comprehend what a big deal Station

Alpha was until today. Their job had turned out to involve wrapping a ton of

equipment and several tons of paper in tarps and moving it out of doors.

Then they spent Thursday tearing the shack apart, making it into a bonfire,

and burning certain books and papers.

"Sheeeyit!" Private Wiley hollers. Only a few of the coolies have

gotten out of the way, or even seen them. But then there is this fantastic

boom from the river, like the sound of a mile thick bamboo pole being

snapped over God's knee. Half a second later there're no coolies in the

street anymore just a lot of boxes with unmanned bamboo poles teeter

tottering on them, bonging into the streets like wind chimes. Above, a furry

mushroom of grey smoke rises from the gunboat. Wiley shifts up to high gear

and floors it. Shaftoe cringes against the truck's door and lowers his head,

hoping that his campy Great War doughboy helmet will be good for something.

Then money boxes start to rupture and explode as the truck rams through

them. Shaftoe peers up through a blizzard of notes and sees giant bamboo

poles soaring and bounding and windmilling toward the waterfront.

The leaves of Shanghai:

Pale doorways in a steel sky.

Winter has begun.

Chapter 1 BARRENS

Let's set the existence of God issue aside for a later volume, and just

stipulate that in some way, self replicating organisms came into existence

on this planet and immediately began trying to get rid of each other, either

by spamming their environments with rough copies of themselves, or by more

direct means which hardly need to be belabored. Most of them failed, and

their genetic legacy was erased from the universe forever, but a few found

some way to survive and to propagate. After about three billion years of

this sometimes zany, frequently tedious fugue of carnality and carnage,

Godfrey Waterhouse IV was born, in Murdo, South Dakota, to Blanche, the wife

of a Congregational preacher named Bunyan Waterhouse. Like every other

creature on the face of the earth, Godfrey was, by birthright, a stupendous

badass, albeit in the somewhat narrow technical sense that he could trace

his ancestry back up a long line of slightly less highly evolved stupendous

badasses to that first self replicating gizmo which, given the number and

variety of its descendants, might justifiably be described as the most

stupendous badass of all time. Everyone and everything that wasn't a

stupendous badass was dead.

As nightmarishly lethal, memetically programmed death machines went,

these were the nicest you could ever hope to meet. In the tradition of his

namesake (the Puritan writer John Bunyan, who spent much of his life in

jail, or trying to avoid it) the Rev. Waterhouse did not preach in any one

place for long. The church moved him from one small town in the Dakotas to

another every year or two. It is possible that Godfrey found the lifestyle

more than a little alienating, for, sometime during the course of his

studies at Fargo Congregational College, he bolted from the fold and, to the

enduring agony of his parents, fell into worldly pursuits, and ended up,

somehow, getting a Ph.D. in Classics from a small private university in

Ohio. Academics being no less nomadic than Congregational preachers, he took

work where he could find it. He became a Professor of Greek and Latin at

Bolger Christian College (enrollment 322) in West Point, Virginia, where the

Mattaponi and Pamunkey Rivers came together to form the estuarial James, and

the loathsome fumes of the big paper mill permeated every drawer, every

closet, even the interior pages of books. Godfrey's young bride, nee Alice

Pritchard, who had grown up following her itinerant preacher father across

the vastnesses of eastern Montana where air smelt of snow and sage threw up

for three months. Six months later she gave birth to Lawrence Pritchard

Waterhouse.

The boy had a peculiar relationship with sound. When a fire engine

passed, he was not troubled by the siren's howl or the bell's clang. But

when a hornet got into the house and swung across the ceiling in a broad

Lissajous, droning almost inaudibly, he cried in pain at the noise. And if

he saw or smelled something that scared him, he would clap his hands over

his ears.

One noise that troubled him not at all was the pipe organ in the chapel

at Bolger Christian College. The chapel itself was nothing worth mentioning,

but the organ had been endowed by the paper mill family and would have

sufficed for a church four times the size. It nicely complemented the

organist, a retired high school math teacher who felt that certain

attributes of the Lord (violence and capriciousness in the Old Testament,

majesty and triumph in the New) could be directly conveyed into the souls of

the enpewed sinners through a kind of frontal sonic impregnation. That he

ran the risk of blowing out the stained glass windows was of no consequence

since no one liked them anyway, and the paper mill fumes were gnawing at the

interstitial lead. But after one little old lady too many staggered down the

aisle after a service, reeling from tinnitus, and made a barbed comment to

the minister about the exceedingly dramatic music, the organist was

replaced.

Nevertheless, he continued to give lessons on the instrument. Students

were not allowed to touch the organ until they were proficient at the piano,

and when this was explained to Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse, he taught

himself in three weeks, how to play a Bach fugue, and signed up for organ

lessons. Since he was only five years old at the time, he was unable to

reach both the manuals and the pedals, and had to play standing or rather

strolling, from pedal to pedal.

When Lawrence was twelve, the organ broke down. That paper mill family

had not left any endowment for maintenance, so the math teacher decided to

have a crack at it. He was in poor health and required a nimble assistant:

Lawrence, who helped him open up the hood of the thing. For the first time

in all those years, the boy saw what had been happening when he had been

pressing those keys.

For each stop each timbre, or type of sound, that the organ could make

(viz. blockflöte, trumpet, piccolo) there was a separate row of pipes,

arranged in a line from long to short. Long pipes made low notes, short

high. The tops of the pipes defined a graph: not a straight line but an

upward tending curve. The organist/math teacher sat down with a few loose

pipes, a pencil, and paper, and helped Lawrence figure out why. When

Lawrence understood, it was as if the math teacher had suddenly played the

good part of Bach's Fantasia and Fugue in G Minor on a pipe organ the size

of the Spiral Nebula in Andromeda the part where Uncle Johann dissects the

architecture of the Universe in one merciless descending ever mutating

chord, as if his foot is thrusting through skidding layers of garbage until

it finally strikes bedrock. In particular, the final steps of the organist's

explanation were like a falcon's dive through layer after layer of pretense

and illusion, thrilling or sickening or confusing depending on what you

were. The heavens were riven open. Lawrence glimpsed choirs of angels

ranking off into geometrical infinity.

The pipes sprouted in parallel ranks from a broad flat box of

compressed air. All of the pipes for a given note but belonging to different

stops lined up with each other along one axis. All of the pipes for a given

stop but tuned at different pitches lined up with each other along the

other, perpendicular axis. Down there in the flat box of air, then, was a

mechanism that got air to the right pipes at the right times. When a key or

pedal was depressed, all of the pipes capable of sounding the corresponding

note would speak, as long as their stops were pulled out.

Mechanically, all of this was handled in a fashion that was perfectly

clear, simple, and logical. Lawrence had supposed that the machine must be

at least as complicated as the most intricate fugue that could be played on

it. Now he had learned that a machine, simple in its design, could produce

results of infinite complexity.

Stops were rarely used alone. They tended to be piled on top of each

other in combinations that were designed to take advantage of the available

harmonics (more tasty mathematics here!). Certain combinations in particular

were used over and over again. Lots of blockflötes, in varying lengths, for

the quiet Offertory, for example. The organ included an ingenious mechanism

called the preset, which enabled the organist to select a particular

combination of stops stops he himself had chosen instantly. He would punch a

button and several stops would bolt out from the console, driven by

pneumatic pressure, and in that instant the organ would become a different

instrument with entirely new timbres.

The next summer both Lawrence and Alice, his mother, were colonized by

a distant cousin a stupendous badass of a virus. Lawrence escaped from it

with an almost imperceptible tendency to drag one of his feet. Alice wound

up in an iron lung. Later, unable to cough effectively, she got pneumonia

and died.

Lawrence's father, Godfrey, freely confessed that he was not equal to

the burdens now laid on his shoulders. He resigned from his position at the

small college in Virginia and moved, with his son, to a small house in

Moorhead, Minnesota, next door to where Bunyan and Blanche had settled.

Later he got a job teaching at a nearby normal school.

At this point, all of the responsible adults in Lawrence's life seemed

to arrive at a tacit agreement that the best way to raise him certainly the

easiest was to leave him alone. On the rare occasions when Lawrence

requested adult intervention in his life, he was usually asking questions

that no one could answer. At the age of sixteen, having found nothing in the

local school system to challenge him, Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse went off

to college. He matriculated at Iowa State College, which among other things

was the site of a Naval ROTC installation in which he was forcibly enrolled.

The Iowa State Naval ROTC had a band, and was delighted to hear that

Lawrence had an interest in music. Since it was hard to drill on the deck of

a dreadnought while playing a pipe organ, they issued him a glockenspiel and

a couple of little dingers.

When not marching back and forth on the flood plain of the Skunk River

making loud dinging noises, Lawrence was majoring in mechanical engineering.

He ended up doing poorly in this area because he had fallen in with a

Bulgarian professor named John Vincent Atanasoff and his graduate student,

Clifford Berry, who were building a machine that was intended to automate

the solution of some especially tedious differential equations.

The basic problem for Lawrence was that he was lazy. He had figured out

that everything was much simpler if, like Superman with his X ray vision,

you just stared through the cosmetic distractions and saw the underlying

mathematical skeleton. Once you found the math in a thing, you knew

everything about it, and you could manipulate it to your heart's content

with nothing more than a pencil and a napkin. He saw it in the curve of the

silver bars on his glockenspiel, saw it in the catenary arch of a bridge and

in the capacitor studded drum of Atanasoff and Berry's computing machine.

Actually pounding on the glockenspiel, riveting the bridge together, or

trying to figure out why the computing machine wasn't working were not as

interesting to him.

Consequently he got poor grades. From time to time, though, he would

perform some stunt on the blackboard that would leave his professor weak in

the knees and the other students baffled and hostile. Word got around.

At the same time, his grandmother Blanche was invoking her extensive

Congregational connections, working the angles on Lawrence's behalf, totally

unbeknownst to him. Her efforts culminated in triumph when Lawrence was

awarded an obscure scholarship, endowed by a St. Paul oat processing heir,

whose purpose was to send Midwestern Congregationalists to the Ivy League

for one year, which (evidently) was deemed a long enough period of time to

raise their IQs by a few crucial points but not long enough to debauch them.

So Lawrence got to be a sophomore in Princeton.

Now Princeton was an august school and going there was a great honor,

but no one got around to mentioning either of these facts to Lawrence, who

had no way of knowing. This had bad and good consequences. He accepted the

scholarship with a faintness of gratitude that infuriated the oat lord. On

the other hand, he adjusted to Princeton easily because it was just another

place . It reminded him of the nicer bits of Virginia, and there were some

nice pipe organs in town, though he was not all that happy with his

engineering homework of bridge designing and sprocket cutting problems. As

always, these eventually came down to math, most of which he could handle

easily. From time to time he would get stuck, though, which led him to the

Fine Hall: the headquarters of the Math Department.

There was a motley assortment of fellows wandering around in Fine Hall,

many sporting British or European accents. Administratively speaking, many

of these fellows were not members of the Math Department at all, but a

separate thing called IAS, which stood for Institute for Advanced something

or other. But they were all in the same building and they all knew a thing

or two about math, so the distinction didn't exist for Lawrence.

Quite a few of these men would pretend shyness when Lawrence sought

their advice, but others were at least willing to hear him out. For example:

he had come up with a way to solve a difficult sprocket tooth shape problem

that, as normally solved by engineers, would require any number of perfectly

reasonable but aesthetically displeasing approximations. Lawrence's solution

would provide exact results. The only draw back was that it would require a

quintillion slide rule operators a quintillion years to solve. Lawrence was

working on a radically different approach that, if it worked, would bring

those figures down to a trillion and a trillion respectively. Unfortunately,

Lawrence was unable to interest anyone at Fine Hall in anything as prosaic

as gears, until all of a sudden he made friends with an energetic British

fellow, whose name he promptly forgot, but who had been doing a lot of

literal sprocket making himself lately. This fellow was trying to build, of

all things, a mechanical calculating machine specifically a machine to

calculate certain values of the Riemann Zeta Function

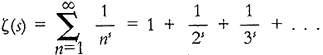

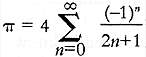

where s is a complex number.

Lawrence found this zeta function to be no more and no less interesting

than any other math problem until his new friend assured him that it was

frightfully important, and that some of the best mathematicians in the world

had been gnawing on it for decades. The two of them ended up staying awake

until three in the morning working out the solution to Lawrence's sprocket

problem. Lawrence presented the results proudly to his engineering

professor, who snidely rejected it, on grounds of practicality, and gave him

a poor grade for his troubles.

Lawrence finally remembered, after several more contacts, that the name

of the friendly Brit was Al something or other. Because Al was a passionate

cyclist, he and Al went on quite a few bicycle rides through the countryside

of the Garden State. As they rode around New Jersey, they talked about math,

and particularly about machines for taking the dull part of math off their

hands.

But Al had been thinking about this subject for longer than Lawrence,

and had figured out that computing machines were much more than just labor

saving devices. He'd been working on a radically different sort of computing

mechanism that would work out any arithmetic problem whatsoever, as long as

you knew how to write the problem down. From a pure logic standpoint, he had

already figured out everything there was to know about this (as yet

hypothetical) machine, though he had yet to build one. Lawrence gathered

that actually building machinery was looked on as undignified at Cambridge

(England, that is, where this Al character was based) or for that matter at

Fine Hall. Al was thrilled to have found, in Lawrence, someone who did not

share this view.

Al delicately asked him, one day, if Lawrence would terribly mind

calling him by his full and proper name, which was Alan and not Al. Lawrence

apologized and said he would try very hard to keep it in mind.

One day a couple of weeks later, as the two of them sat by a running

stream in the woods above the Delaware Water Gap, Alan made some kind of an

outlandish proposal to Lawrence involving penises. It required a great deal

of methodical explanation, which Alan delivered with lots of blushing and

stuttering. He was ever so polite, and several times emphasized that he was

acutely aware that not everyone in the world was interested in this sort of

thing.

Lawrence decided that he was probably one of those people.

Alan seemed vastly impressed that Lawrence had paused to think about it

at all and apologized for putting him out. They went directly back to a

discussion of computing machines, and their friendship continued unchanged.

But on their next bicycle ride an overnight camping trip to the Pine Barrens

they were joined by a new fellow, a German named Rudy von something or

other.

Alan and Rudy's relationship seemed closer, or at least more

multilayered, than Alan and Lawrence's. Lawrence concluded that Alan's penis

scheme must have finally found a taker.

It got Lawrence to thinking. From an evolution standpoint, what was the

point of having people around who were not inclined to have offspring? There

must be some good, and fairly subtle, reason for it.

The only thing he could work out was that it was groups of people

societies rather than individual creatures, who were now trying to out

reproduce and/or kill each other, and that, in a society, there was plenty

of room for someone who didn't have kids as long as he was up to something

useful.

Alan and Rudy and Lawrence rode south, anyway, looking for the Pine

Barrens. After a while the towns became very far apart, and the horse farms

gave way to a low stubble of feeble, spiny trees that appeared to extend all

the way to Florida blocking their view, but not the head wind. "Where are

the Pine Barrens I wonder?" Lawrence asked a couple of times. He even

stopped at a gas station to ask someone that question. His companions began

to make fun of him.

"Vere are ze Pine Barrens?" Rudy inquired, looking about quizzically.

"I should look for something rather barren looking, with numerous pine

trees," Alan mused.

There was no other traffic and so they had spread out across the road

to pedal three abreast, with Alan in the middle.

"A forest, as Kafka would imagine it," Rudy muttered.

By this point Lawrence had figured out that they were, in fact, in the

Pine Barrens. But he didn't know who Kafka was. "A mathematician?" he

guessed.

"Zat is a scary sing to sink of," Rudy said.

"He is a writer," Alan said. "Lawrence, please don't be offended that I

ask you this, but: do you recognize any other people's names at all? Other

than family and close friends, I mean."

Lawrence must have looked baffled. "I'm trying to figure out whether it

all comes from in here," Alan said, reaching out to rap his knuckles on the

side of Lawrence's head, "or do you sometimes take in new ideas from other

human beings?"

"When I was a little boy, I saw angels in a church in Virginia,"

Lawrence said, "but I think that they came from inside my head."

"Very well," Alan said.

But later Alan had another go at it. They had reached the fire lookout

tower and it had been a thunderous disappointment: just an alienated

staircase leading nowhere, and a small cleared area below that was glittery

with shards of liquor bottles. They pitched their tent by the side of a pond

that turned out to be full of rust colored algae that stuck to the hairs on

their bodies. Then there was nothing left to do but drink schnapps and talk

about math.

Alan said, "Look, it's like this: Bertrand Russell and another chap

named Whitehead wrote Principia Mathematica .

"Now I know you're pulling my leg," Waterhouse said. "Even I know that

Sir Isaac Newton wrote that ."

"Newton wrote a different book, also called Principia Mathematica ,

which isn't really about mathematics at all; it's about what we would today

call physics."

"Then why did he call it Principia Mathematica?"

"Because the distinction between mathematics and physics wasn't

especially clear in Newton's day "

"Or maybe even in zis day," Rudy said.

" which is directly relevant to what I'm talking about," Alan

continued. "I am talking about Russell's P.M., in which he and Whitehead

started absolutely from scratch, I mean from nothing, and built it all up

all mathematics from a small number of first principles. And why I am

telling you this, Lawrence, is that Lawrence! Pay attention!"

"Hmmm?"

"Rudy take this stick, here that's right and keep a close eye on

Lawrence, and when he gets that foggy look on his face, poke him with it!"

"Zis is not an English school, you can't do zese kind of sing."

"I'm listening," Lawrence said.

"What came out of P.M., which was terrifically radical, was the ability

to say that all of math, really, can be expressed as a certain ordering of

symbols."

"Leibniz said it a long time before zen!" protested Rudy.

"Er, Leibniz invented the notation we use for calculus, but "

"I'm not talking about zat!"

"And he invented matrices, but "

"I'm not talking about zat eezer!"

"And he did some work with binary arithmetic, but "

"Zat is completely different!"

"Well, what the hell are you talking about, then, Rudy?"

"Leibniz invented ze basic alphabet wrote down a set of symbols, for

expressing statements about logic."

"Well, I wasn't aware that Herr Leibniz counted formal logic among his

interests, but "

"Of course! He wanted to do what Russell and Whitehead did, except not

just with mathematics, but with everything in ze whole world!"

"Well, from the fact that you are the only man on the planet, Rudy, who

seems to know about this undertaking of Leibniz's, can we assume that he

failed?"

"You can assume anything that pleases your fancy, Alan," Rudy

responded, "but I am a mathematician and I do not assume anything."

Alan sighed woundedly, and gave Rudy a Significant Look which

Waterhouse assumed meant that there would be trouble later. "If I may just

make some headway, here," he said, "all I'm really trying to get you to

agree on, is that mathematics can be expressed as a series of symbols," (he

snatched the Lawrence poking stick and began drawing things like + = 3)

[square root of 1][pi] in the dirt) "and frankly I could not care less

whether they happen to be Leibniz's symbols, or Russell's, or the hexagrams

of the I Ching...."

"Leibniz was fascinated by the I Ching!" Rudy began.

"Shut up about Leibniz for a moment, Rudy, because look here: You Rudy

and I are on a train, as it were, sitting in the dining car, having a nice

conversation, and that train is being pulled along at a terrific clip by

certain locomotives named The Bertrand Russell and Riemann and Euler and

others. And our friend Lawrence is running alongside the train, trying to

keep up with us it's not that we're smarter than he is, necessarily, but

that he's a farmer who didn't get a ticket. And I, Rudy, am simply reaching

out through the open window here, trying to pull him onto the fucking train

with us so that the three of us can have a nice little chat about

mathematics without having to listen to him panting and gasping for breath

the whole way."

"All right, Alan."

"Won't take a minute if you will just stop interrupting."

"But there is a locomotive too named Leibniz."

"Is it that you don't think I give enough credit to Germans? Because I

am about to mention a fellow with an umlaut."

"Oh, would it be Herr Türing?" Rudy said slyly.

"Herr Türing comes later. I was actually thinking of Gödel."

"But he's not German! He's Austrian!"

"I'm afraid that it's all the same now, isn't it?"

"Ze Anschluss wasn't my idea, you don't have to look at me that way, I

think Hitler is appalling."

"I've heard of Gödel," Waterhouse put in helpfully. "But could we back

up just a sec?"

"Of course Lawrence."

"Why bother? Why did Russell do it? Was there something wrong with

math? I mean, two plus two equals four, right?"

Alan picked up two bottlecaps and set them down on the ground. "Two.

One two. Plus " He set down two more. "Another two. One two. Equals four.

One two three four."

"What's so bad about that?" Lawrence said.

"But Lawrence when you really do math, in an abstract way, you're not

counting bottlecaps, are you?"

"I'm not counting anything. "

Rudy broke the following news: "Zat is a very modern position for you

to take."

"It is?"

Alan said, "There was this implicit belief, for a long time, that math

was a sort of physics of bottlecaps. That any mathematical operation you

could do on paper, no matter how complicated, could be reduced in theory,

anyway to messing about with actual physical counters, such as bottlecaps,

in the real world."

"But you can't have two point one bottlecaps."

"All right, all right, say we use bottlecaps for integers, and for real

numbers like two point one, we use physical measurements, like the length of

this stick." Alan tossed the stick down next to the bottlecaps.

"Well what about pi, then? You can't have a stick that's exactly pi

inches long."

"Pi is from geometry ze same story," Rudy put in.

"Yes, it was believed that Euclid's geometry was really a kind of

physics, that his lines and so on represented properties of the physical

world. But you know Einstein?"

"I'm not very good with names."

"That white haired chap with the big mustache?"

"Oh, yeah," Lawrence said dimly, "I tried to ask him my sprocket

question. He claimed he was late for an appointment or something."

"That fellow has come up with a general relativity theory, which is

sort of a practical application, not of Euclid's, but of Riemann's geometry

"

"The same Riemann of your zeta function?"

"Same Riemann, different subject. Now let's not get sidetracked here

Lawrence "

"Riemann showed you could have many many different geometries that were

not the geometry of Euclid but that still made sense internally," Rudy

explained.

"All right, so back to P.M. then," Lawrence said.

"Yes! Russell and Whitehead. It's like this: when mathematicians began

fooling around with things like the square root of negative one, and

quaternions, then they were no longer dealing with things that you could

translate into sticks and bottlecaps. And yet they were still getting sound

results."

"Or at least internally consistent results," Rudy said.

"Okay. Meaning that math was more than a physics of bottlecaps."

"It appeared that way, Lawrence, but this raised the question of was

mathematics really true or was it just a game played with symbols? In other

words are we discovering Truth, or just wanking?"

"It has to be true because if you do physics with it, it all works out!

I've heard of that general relativity thing, and I know they did experiments

and figured out it was true."

"Ze great majority of mathematics does not lend itself to experimental

testing," Rudy said.

"The whole idea of this project is to sever the ties to physics," Alan

said.

"And yet not to be yanking ourselves."

"That's what P.M. was trying to do?"

"Russell and Whitehead broke all mathematical concepts down into

brutally simple things like sets. From there they got to integers, and so

on.

"But how can you break something like pi down into a set?"

"You can't," Alan said, "but you can express it as a long string of

digits. Three point one four one five nine, and so on."

"And digits are integers," Rudy said.

"But no fair! Pi itself is not an integer!"

"But you can calculate the digits of pi, one at a time, by using

certain formulas. And you can write down the formulas like so!" Alan

scratched this in the dirt:

where s is a complex number.

Lawrence found this zeta function to be no more and no less interesting

than any other math problem until his new friend assured him that it was

frightfully important, and that some of the best mathematicians in the world

had been gnawing on it for decades. The two of them ended up staying awake

until three in the morning working out the solution to Lawrence's sprocket

problem. Lawrence presented the results proudly to his engineering

professor, who snidely rejected it, on grounds of practicality, and gave him

a poor grade for his troubles.

Lawrence finally remembered, after several more contacts, that the name

of the friendly Brit was Al something or other. Because Al was a passionate

cyclist, he and Al went on quite a few bicycle rides through the countryside

of the Garden State. As they rode around New Jersey, they talked about math,

and particularly about machines for taking the dull part of math off their

hands.

But Al had been thinking about this subject for longer than Lawrence,

and had figured out that computing machines were much more than just labor

saving devices. He'd been working on a radically different sort of computing

mechanism that would work out any arithmetic problem whatsoever, as long as

you knew how to write the problem down. From a pure logic standpoint, he had

already figured out everything there was to know about this (as yet

hypothetical) machine, though he had yet to build one. Lawrence gathered

that actually building machinery was looked on as undignified at Cambridge

(England, that is, where this Al character was based) or for that matter at

Fine Hall. Al was thrilled to have found, in Lawrence, someone who did not

share this view.

Al delicately asked him, one day, if Lawrence would terribly mind

calling him by his full and proper name, which was Alan and not Al. Lawrence

apologized and said he would try very hard to keep it in mind.

One day a couple of weeks later, as the two of them sat by a running

stream in the woods above the Delaware Water Gap, Alan made some kind of an

outlandish proposal to Lawrence involving penises. It required a great deal

of methodical explanation, which Alan delivered with lots of blushing and

stuttering. He was ever so polite, and several times emphasized that he was

acutely aware that not everyone in the world was interested in this sort of

thing.

Lawrence decided that he was probably one of those people.

Alan seemed vastly impressed that Lawrence had paused to think about it

at all and apologized for putting him out. They went directly back to a

discussion of computing machines, and their friendship continued unchanged.

But on their next bicycle ride an overnight camping trip to the Pine Barrens

they were joined by a new fellow, a German named Rudy von something or

other.

Alan and Rudy's relationship seemed closer, or at least more

multilayered, than Alan and Lawrence's. Lawrence concluded that Alan's penis

scheme must have finally found a taker.

It got Lawrence to thinking. From an evolution standpoint, what was the

point of having people around who were not inclined to have offspring? There

must be some good, and fairly subtle, reason for it.

The only thing he could work out was that it was groups of people

societies rather than individual creatures, who were now trying to out

reproduce and/or kill each other, and that, in a society, there was plenty

of room for someone who didn't have kids as long as he was up to something

useful.

Alan and Rudy and Lawrence rode south, anyway, looking for the Pine

Barrens. After a while the towns became very far apart, and the horse farms

gave way to a low stubble of feeble, spiny trees that appeared to extend all

the way to Florida blocking their view, but not the head wind. "Where are

the Pine Barrens I wonder?" Lawrence asked a couple of times. He even

stopped at a gas station to ask someone that question. His companions began

to make fun of him.

"Vere are ze Pine Barrens?" Rudy inquired, looking about quizzically.

"I should look for something rather barren looking, with numerous pine

trees," Alan mused.

There was no other traffic and so they had spread out across the road

to pedal three abreast, with Alan in the middle.

"A forest, as Kafka would imagine it," Rudy muttered.

By this point Lawrence had figured out that they were, in fact, in the

Pine Barrens. But he didn't know who Kafka was. "A mathematician?" he

guessed.

"Zat is a scary sing to sink of," Rudy said.

"He is a writer," Alan said. "Lawrence, please don't be offended that I

ask you this, but: do you recognize any other people's names at all? Other

than family and close friends, I mean."

Lawrence must have looked baffled. "I'm trying to figure out whether it

all comes from in here," Alan said, reaching out to rap his knuckles on the

side of Lawrence's head, "or do you sometimes take in new ideas from other

human beings?"

"When I was a little boy, I saw angels in a church in Virginia,"

Lawrence said, "but I think that they came from inside my head."

"Very well," Alan said.

But later Alan had another go at it. They had reached the fire lookout

tower and it had been a thunderous disappointment: just an alienated

staircase leading nowhere, and a small cleared area below that was glittery

with shards of liquor bottles. They pitched their tent by the side of a pond

that turned out to be full of rust colored algae that stuck to the hairs on

their bodies. Then there was nothing left to do but drink schnapps and talk

about math.

Alan said, "Look, it's like this: Bertrand Russell and another chap

named Whitehead wrote Principia Mathematica .

"Now I know you're pulling my leg," Waterhouse said. "Even I know that

Sir Isaac Newton wrote that ."

"Newton wrote a different book, also called Principia Mathematica ,

which isn't really about mathematics at all; it's about what we would today

call physics."

"Then why did he call it Principia Mathematica?"

"Because the distinction between mathematics and physics wasn't

especially clear in Newton's day "

"Or maybe even in zis day," Rudy said.

" which is directly relevant to what I'm talking about," Alan

continued. "I am talking about Russell's P.M., in which he and Whitehead

started absolutely from scratch, I mean from nothing, and built it all up

all mathematics from a small number of first principles. And why I am

telling you this, Lawrence, is that Lawrence! Pay attention!"

"Hmmm?"

"Rudy take this stick, here that's right and keep a close eye on

Lawrence, and when he gets that foggy look on his face, poke him with it!"

"Zis is not an English school, you can't do zese kind of sing."

"I'm listening," Lawrence said.

"What came out of P.M., which was terrifically radical, was the ability

to say that all of math, really, can be expressed as a certain ordering of

symbols."

"Leibniz said it a long time before zen!" protested Rudy.

"Er, Leibniz invented the notation we use for calculus, but "

"I'm not talking about zat!"

"And he invented matrices, but "

"I'm not talking about zat eezer!"

"And he did some work with binary arithmetic, but "

"Zat is completely different!"

"Well, what the hell are you talking about, then, Rudy?"

"Leibniz invented ze basic alphabet wrote down a set of symbols, for

expressing statements about logic."

"Well, I wasn't aware that Herr Leibniz counted formal logic among his

interests, but "

"Of course! He wanted to do what Russell and Whitehead did, except not

just with mathematics, but with everything in ze whole world!"

"Well, from the fact that you are the only man on the planet, Rudy, who

seems to know about this undertaking of Leibniz's, can we assume that he

failed?"

"You can assume anything that pleases your fancy, Alan," Rudy

responded, "but I am a mathematician and I do not assume anything."

Alan sighed woundedly, and gave Rudy a Significant Look which

Waterhouse assumed meant that there would be trouble later. "If I may just

make some headway, here," he said, "all I'm really trying to get you to

agree on, is that mathematics can be expressed as a series of symbols," (he

snatched the Lawrence poking stick and began drawing things like + = 3)

[square root of 1][pi] in the dirt) "and frankly I could not care less

whether they happen to be Leibniz's symbols, or Russell's, or the hexagrams

of the I Ching...."

"Leibniz was fascinated by the I Ching!" Rudy began.

"Shut up about Leibniz for a moment, Rudy, because look here: You Rudy

and I are on a train, as it were, sitting in the dining car, having a nice

conversation, and that train is being pulled along at a terrific clip by

certain locomotives named The Bertrand Russell and Riemann and Euler and

others. And our friend Lawrence is running alongside the train, trying to

keep up with us it's not that we're smarter than he is, necessarily, but

that he's a farmer who didn't get a ticket. And I, Rudy, am simply reaching

out through the open window here, trying to pull him onto the fucking train

with us so that the three of us can have a nice little chat about

mathematics without having to listen to him panting and gasping for breath

the whole way."

"All right, Alan."

"Won't take a minute if you will just stop interrupting."

"But there is a locomotive too named Leibniz."

"Is it that you don't think I give enough credit to Germans? Because I

am about to mention a fellow with an umlaut."

"Oh, would it be Herr Türing?" Rudy said slyly.

"Herr Türing comes later. I was actually thinking of Gödel."

"But he's not German! He's Austrian!"

"I'm afraid that it's all the same now, isn't it?"

"Ze Anschluss wasn't my idea, you don't have to look at me that way, I

think Hitler is appalling."

"I've heard of Gödel," Waterhouse put in helpfully. "But could we back

up just a sec?"

"Of course Lawrence."

"Why bother? Why did Russell do it? Was there something wrong with

math? I mean, two plus two equals four, right?"

Alan picked up two bottlecaps and set them down on the ground. "Two.

One two. Plus " He set down two more. "Another two. One two. Equals four.

One two three four."

"What's so bad about that?" Lawrence said.

"But Lawrence when you really do math, in an abstract way, you're not

counting bottlecaps, are you?"

"I'm not counting anything. "

Rudy broke the following news: "Zat is a very modern position for you

to take."

"It is?"

Alan said, "There was this implicit belief, for a long time, that math

was a sort of physics of bottlecaps. That any mathematical operation you

could do on paper, no matter how complicated, could be reduced in theory,

anyway to messing about with actual physical counters, such as bottlecaps,

in the real world."

"But you can't have two point one bottlecaps."

"All right, all right, say we use bottlecaps for integers, and for real

numbers like two point one, we use physical measurements, like the length of

this stick." Alan tossed the stick down next to the bottlecaps.

"Well what about pi, then? You can't have a stick that's exactly pi

inches long."

"Pi is from geometry ze same story," Rudy put in.

"Yes, it was believed that Euclid's geometry was really a kind of

physics, that his lines and so on represented properties of the physical

world. But you know Einstein?"

"I'm not very good with names."

"That white haired chap with the big mustache?"

"Oh, yeah," Lawrence said dimly, "I tried to ask him my sprocket

question. He claimed he was late for an appointment or something."

"That fellow has come up with a general relativity theory, which is